The first time I saw Lynyrd Skynyrd guitarist Allen Collins was in 1969, when I went with a group of hippies to the Comic Book Club in downtown Jacksonville, where One Percent was the house band, to score some acid.

Collins was leaning against a wall outside the club, long and lean, dressed entirely in white, looking like John Lennon on the cover of The Beatles’ Abbey Road. This getup became Collins’ trademark for a time; he even wore white tennis shoes, the kind women wore. This was topped by a huge head of shoulder-length, curly hair.

A few days later my friends and I ate the acid. It was Friday night. The five of us wound up at the Sugar Bowl, a teen club in a working-class subdivision called Cedar Hills, where several prominent musicians were raised, including Collins and future Skynyrd members Leon Wilkeson and Billy Powell, guitarist Jeff Carlisi (of .38 Special), singer-guitarist Don Barnes (also of .38), and keyboardist Kevin Elson (later sound mixer, recording engineer and producer).

One Percent, soon to become Lynyrd Skynyrd, was performing that night. There was a scuffle; some local rednecks had invaded. They were harassing hippies and got into a battle with an off-duty cop who served as a security guard. Someone pulled a knife. More cops materialized. Since we were just starting to get off on the acid, my friends and I hauled ass out of there.

I ran into Allen Collins again in 1978, a year after the infamous plane crash, when my second wife and I were living in a small house in Murray Hill.

We were eating at Church’s Chicken on Cassat Avenue and Plymouth Street, when in walks Collins, who gets in line behind me. He seemed to recognize me. I told him I knew Wilkeson, whom I had met at the Forrest Inn, while he was with a group called King James Version. Collins sat down with my and my wife, and as we were leaving he offhandedly asked if I knew where he could buy a junk car for about a hundred bucks. He said he liked to take them out in to the woods and roll them. This was his idea of fun.

Not long later, I met Marion “Sister” Van Zant up the street at Dunkin’ Donuts, where she worked as a waitress. This was a year after Skynyrd’s plane crash. She invited me to the Van Zant house and introduced to sons Donnie and Johnny. I had already met Donnie in 1970 when I auditioned at Kevin Elson’s parents’ house for Sweet Rooster, a group that morphed into .38 Special.

I told Sister about meeting Collins at the chicken place. She said Collins was a disaster behind the wheel and told me a story Johnny Van Zant had related: he had been pulling out of the Krystal on San Juan Avenue recently and was run off the road, nearly hit, by a crazy driver coming around the corner too fast in the wrong lane. Johnny honked at the guy, and the guy gave him the finger. The offending driver was Collins, of course.

In early 1985, I was working with Filthy Phil Price and drummer-singer Carl De Blasio at Mac’s Mustang Lounge.

One night Allen Collins came in the bar with his drummer-driver Steve Reynolds.

Collins apparently liked what he heard because the pair came back the next night and again the next weekend. I know this was late February, because Collins threw a pie at me on my birthday—Skynyrd had a tradition that anyone having a birthday got a pie in the face. I’m on the bandstand; Collins comes rushing toward me with a key-lime pie; I duck; he misses me and flings key-lime goo into my Echoplex. He laughs. I fail to see any humor in this. That unit cost me $150, which was a lot of money for me at the time, and was ruined beyond repair. But he meant it affectionately.

Collins wanted to put a new Allen Collins Band together, and he wanted me as lead singer and second guitarist. He also needed a bass player; Price was offered the position. He already had a drummer—who doubled as his chauffeur—so De Blasio was left out.

The reason Collins needed a chauffeur was because he’d had his license revoked and was not allowed to drive. Reynolds and Collins picked Price and me up to bring us to Collins’ estate in Mandarin. On the way, Collins decides he wants to drive. Here we are, doing 50 miles per hour through a 7-11 parking lot. Trying to stay calm—I realize he is messing with our heads—I say, “Allen, who is going to clean up your nice leather seats?”

“What do you mean?” he replies.

“I mean you are scaring the shit out of us.”

He cackles.

“Allen, if you want to kill yourself, that’s fine, but please don’t take us with you.”

He turns back to face us, left hand on the wheel, still doing 50 mph. “Ah, ya buncha pussies.”

Scuffling to survive, Price, De Blasio and I travel to Vidalia, Ga., to become the weekend house band at the Golden Nugget, a medium-sized nightclub. After a few weeks Di Blasio disappeared, perhaps because he was resentful about not being included in the new Collins project. Price and I came into the club one afternoon and the drums and sound system, which De Blasio owned, were gone.

Fortunately, there was a band down the street with an excellent drummer who also sang very well and owned a decent sound system. His name was Scott Sisson. He’d just had a falling out with a band member who’d disparaged his wife. Scott came over to our band that afternoon and literally saved the day.

Collins and Reynolds drove up from Jacksonville to see us on a Saturday. We gathered at Sisson’s house in Lyons that afternoon. Collins taught me how to play the riff to the “The Last Time” the correct way. Keith Richards, he said, had shown it to him personally (this was a credible claim since the Stones and Skynyrd at one point shared a manager, Peter Rudge).

Collins also claimed he had boinked Chaka Khan on Skynyrd’s tour bus. This is notable because certain Skynyrd members were notorious bigots. However, Collins did not appear to be one of them.

Collins spots some pills on a coffee table, snatches a handful and gulps them down. Sisson’s wife says, “Allen, you eejit! ‘Em were my burf-control pills.” Allen grins like the Cheshire Cat and shrugs.

I said something Collins didn’t like—can’t recall what—and he retorts, “Fuck you, you Jimmy Dougherty-lookin’ motherfucker,” and hurls a half-full Heineken bottle at my head, which goes whizzing by my ear (Jimmy Dougherty was the previous lead singer for the Allen Collins Band). The bottle sails butt-first through the drywall, landing with its neck sticking out.

I should have quit then and there, but the lure of being in a big-time, touring rock band was too powerful.

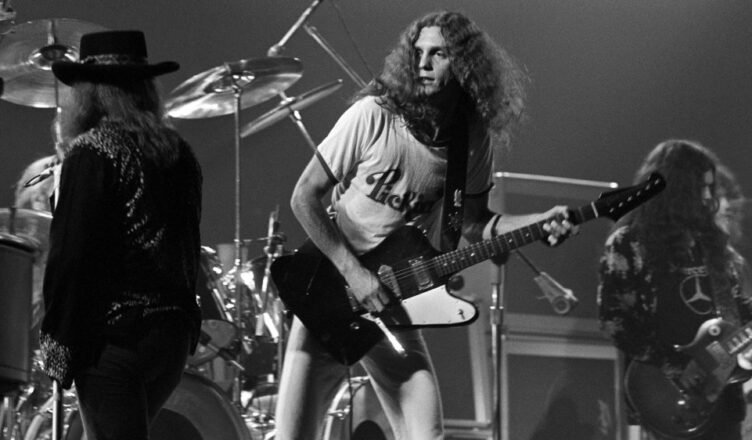

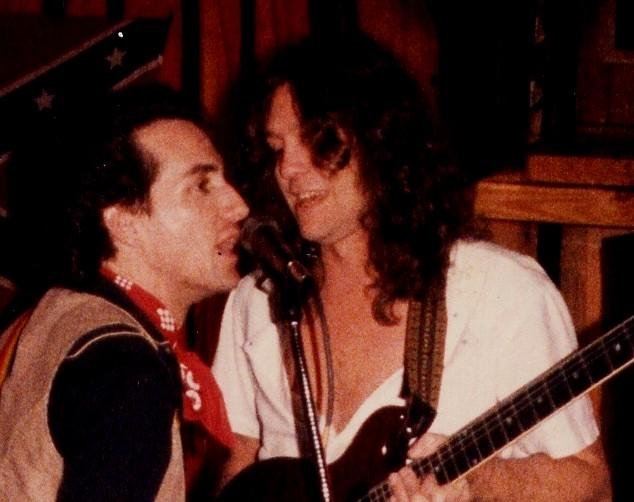

Collins was to “sit in” with us that night at the club. Word got around, and the place was packed with Skynyrd fans. Collins emerged from the bathroom, stumbling up onto the bandstand, which had a railing in front. Collins couldn’t even get his guitar—a very valuable 1957 Gibson Les Paul—on. I had to hold it up for him and fasten his strap (see photo).

I take the mic and ask the audience to welcome Allen Collins to Vidalia. The crowd roars.

Collins grabs the mic. “You buncha fuckin’ punks,” he rails. “I’ll kick anyone’s ass in this room right now.”

People are looking at each other wondering what to think.

Assuming this is some kind of redneck humor, I grab the mic and say, “Can y’all say ‘Fuck you, Allen’?”

“Fuck you, Allen!” the audience roars in unison.

Everyone laughs, including Collins.

We start playing “The Last Time.” During the intro, Collins falls headfirst over the railing and hits the floor with his face. He is out cold with his feet still up on the railing, sort of hanging there. His beautiful Les Paul is broken, the headstock severed from the neck, dangling by the strings.

I had been trained never to stop playing in the middle of a song no matter what happens, because if there’s a melee, stopping will draw everyone’s attention, whereas if you keep playing, a lot of people won’t notice. I was afraid stopping would draw more attention to the situation. So we kept going and left him lying there face-down for what seemed like a very long time. Someone from the audience eventually got up and helped him.

Collins gets up and dusts himself off. He wanders over to a table where there is a birthday cake set out. He grabs a piece of cake and hurls it at the birthday girl, who doesn’t know about the pie-in-the-face tradition. She ducks; he misses. She complains to her boyfriend, a big guy in a ball cap.

Reynolds grabs Collins and shuffles him out the door and into Collins’ white Lincoln. They go to the motel, get their stuff, and head back to Jacksonville, a two-hour drive. We don’t hear a thing that night or the next day from either of them.

Price and I are driving back home to our apartment in Jacksonville. There’s a short-cut on State Road 15 running through Blackshear that leads back to U.S. 1. There used to be a stop sign at this corner fastened to a four-by-four post stuck in the ground. But now the post is broken off about two feet up, no stop sign in sight.

Price looks at the stump and says, “I’ll bet you anything Allen did that.”

“Did what?” I reply.

“Look where the post is whacked off,” he says. “About the height of a car bumper. I bet Allen was driving and ran over it.”

On Monday we get called to a rehearsal at Collins’ house on Plummer Grant Road. Reynolds opens the garage door to get something out of the Continental’s trunk. There is a huge dent in the trunk’s lid.

“How’d that happen?” I ask. Price looks over at me, eyebrows arching.

“Allen decided to drive home,” Reynolds replies. “He hit a stop sign on the way back. It broke off, went flying up in the air over the top of the car and landed right there.”

Price busts out laughing. “I told you,” he says. We swore we would never again get into a car with Collins at the wheel.

We go into the rehearsal room; Collins is there with a beautiful sunburst Rickenbacker. I was to co-write some songs with him, which meant he would come up with the germ of an idea and I would flesh it out. He began to sing me something he was working on. I was amazed at how much he sounded like Lou Reed—whom I liked—and told him so. Collins, however, apparently loathed Reed—I think he assumed Reed was gay—and flung the Rickenbacker at me. Lucky for him I caught it in midair, before it too hit the wall.

After he cools down, he picks up a Stratocaster and we start rehearsing “Sweet Home, Alabama.” It’s only 7 p.m., and he’s already too drunk to play. We’re all embarrassed for him. He puts his guitar down and says, “I’ll be right back.” After waiting an hour, we go into the house to look for him. There he is, passed out in a La-Z-Boy with a bottle of Jack beside him. There is a thick, black steak scorching in a skillet, filling the kitchen with smoke.

Collins had every reason to self-medicate. Not only had his band been destroyed in a plane crash, he himself had suffered a broken neck and nearly lost an arm. On top of all this he’d had to deal with the shock of his wife’s death three later. “That’s what destroyed him,” Skynyrd keyboardist Billy Powell (who died in 2009) told interviewer Marley Brant. “He dove into a bottle and never came out.”

Collins was actually a sweet guy

if you could catch him sober, which might be for about 20 minutes after he woke up. The only other times I saw him behave gently was around his daughters, whom he adored and they him.

In any case, I could not stomach working with him anymore. I had other fish to fry. Atlanta label Hottrax, which distributed my record, “Fuck Everybody,” called and said the song was building a buzz and that I should get my own band together and bring it to Atlanta for a showcase. So that’s what Price and I concentrated on. This was late summer in 1985.

I really don’t know—no one does—what happened on the night of January 29, 1986, but knowing Collins I have pretty fair idea. Collins was driving his new Ford Thunderbird home down Plummer Grant Road with his fiancée, Debra Jean Watts, in the passenger seat. He was not supposed to be driving. I am speculating—this is an educated guess, taken from experience—that she probably yelled at him to slow down, pull over, stop acting so stupid. He probably got distracted and swerved. Maybe she grabbed the wheel. Maybe they got into a tussle doing 80 miles per hour.

In any case, the car spun out of control and ended up in a culvert. Both were thrown through the driver’s-side window. Watts died from her injuries.

Collins suffered a broken back. He wound up paralyzed from the waist down. Mutual friends told me that there might have been a chance for recovery had he taken his physical therapy seriously.

Collins was charged with DUI manslaughter. At first he denied having been driving, but fibers from his shirt, embedded in the driver’s-side door, indicated otherwise, plus there was a huge bruise on his right side where Watts had collided with him.

Reynolds, who was very close to Collins and Collins’ father, Larkin, doesn’t agree with the conclusions of the police report. Neither did Larkin Collins. Reynolds says Larkin told him both Collins and Watts were ejected out the passenger side and that Collins went out the window before Watts.

It was clear to most people who knew him that it was not safe to get into a vehicle with Collins, even if he wasn’t driving. While sitting in the passenger seat, Collins enjoyed scaring the hell out of drivers—and anyone else in the car.

“He would stomp his foot down on top of mine [on the gas pedal],” Reynolds says. “The next thing I knew we’d be doing 100.” Collins would also yank the steering wheel. “He most likely did that while Debra was driving,” Reynolds adds. ”I was wise to his pranks and could see them coming, but she wasn’t ready for that.”

Collins finally pled no contest, claiming he had no memory of the incident. Taking his injuries into consideration, the assistant state attorney, Wayne Ellis, asked for leniency. In addition to probation, the judge ordered Collins to organize and participate in an anti-drunk-driving campaign.

In 1987, Collins and his father decided to re-form Lynyrd Skynyrd for a “tribute tour.” The remaining Skynyrd members agreed, along with Ronnie Van Zant’s younger brother, Johnny, who would take center stage. Collins served as musical director. He chose Randall Hall, who had been in the Allen Collins Band, as his replacement.

To honor his probation, he appeared, wheel-chair bound, before every show to provide a short lecture on the consequences of drinking and driving. Collins developed chronic pneumonia and died in January 1990.

The band, however, carried on with the help of several replacements taking the place of dying members—guitarist Gary Rossington is the only remaining founder—and has been touring regularly since. It’s still a money machine, and the southern-rock style forged in Jacksonville refuses to die. It’s possible the group might not have gotten back together without Collins’ urging.