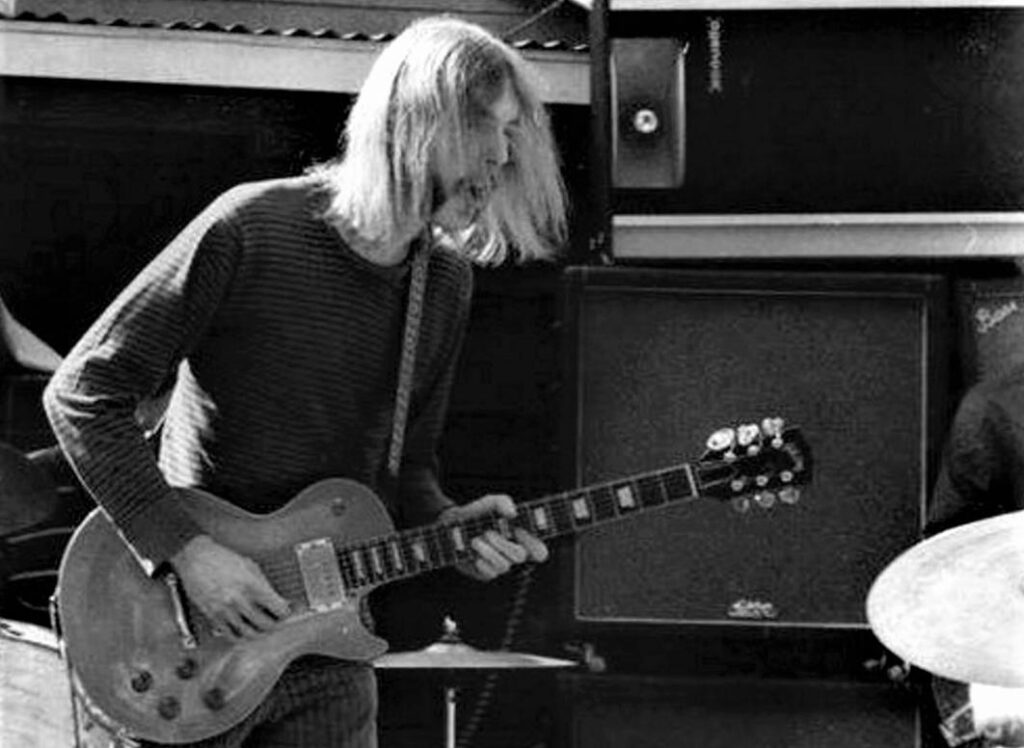

The below passage “Heckling Duane Allman” is an excerpt from Michael Ray Fitzgerald‘s new book, Guitar Greats of Jacksonville. Photo credit: Charles Faubion.

Someone in the trailer park where I lived with my grandmother in Orange Park told me about a guy down the lane who played guitar and was really good. His name was Paul Glass. I took it upon myself to pop in on him. He was a year older than I and had dropped out of school.

He was already a part-time professional musician, playing on weekends with Cedar Hills guitarist Jeff Carlisi—who would later go on to legendary status—in a group called Doomsday Refreshment Committee. While Glass’ parents were at work, he hung out in the trailer all day with the shades drawn, practicing guitar, waiting for his weekend gigs.

I knocked on the door. Glass stuck his head out with his long, stringy hair and said brusquely, “What?” I said, “I heard you play guitar.” He replied, “Yeah.” I raised up the black guitar case I was carrying and said, “Look what I got.” He said, “Let me see it.”

He opened the door, and I followed him into the dark room. I pulled the guitar out of its case. As he sat on the couch and played my SG masterfully he sneered, “You don’t deserve this guitar.” I was taken aback at his asperity, but my feelings weren’t hurt because I reckoned this meant I had made a damn good choice.

Glass taught me the secret of playing blues and rock: super-light-gauge strings, specifically Ernie Ball Extra-Slinkies. Someone with small hands like mine could not pull strings the way Eric Clapton did without using super-light strings. This unlocked the door, and I spent nearly every night practicing till the wee hours. I would go back to Glass’s trailer many more times; we became friends of sorts.

Glass, who owned a blond Epiphone Casino like John Lennon’s, wanted to borrow my SG for his gigs. Of course there was no way I was letting it out of my sight. So he came up with a plan: I could come along to the gigs and keep an eye on it. I got to meet and hang out with Carlisi and other musicians from Jacksonville’s Westside and see up-close how all this was done. Still, I was not really good enough to play in a band and remained inhibited. Even more daunting, I had no amplifier to speak of—only a tiny, battery-powered practice amp.

Glass taught me about the local guitar culture and its deities.

He talked about a group from Daytona called the Allman Joys, which featured Duane Allman, considered one of the top players in Florida. Glass insisted, however, that the main man was Dickey Betts, who lived in Riverside and played around the area often.

Betts was from Bradenton, south of Tampa. His group, the Blues Messengers, had come to Jacksonville the previous year to work as the house band at a nightclub called the Scene. The owner, Leonard Renzler, reputedly insisted the group change its name to the Second Coming because—he thought—bassist Berry Oakley looked like Jesus with his long hair and beard.

Glass and I journeyed all over the area to see Betts at every opportunity. One night we hitch-hiked to a Westside district called Paxon to see the Second Coming at the Woodstock Youth Center. This was a rather rough, working-class area, and with our long hair—his was nearly down to his shoulders—we had to avoid the local rednecks, which is pretty difficult when you’re standing out on the street with your thumb sticking out. When we saw a muscle car coming, we would duck back onto the sidewalk and look the other way.

Admission was a bit steep, two dollars. We couldn’t wait to hear Betts play “Crossroads.” He could give Clapton a run for his money! But to our dismay Betts didn’t play many solos that night. A diffident young man with stringy, blondish hair was “sitting in” on guitar and hogging the solos.

We were irate. “Let Dickey play!” we shouted. “We came to hear Dickey!” Even though Glass had mentioned Duane Allman to me, he didn’t recognize the guitarist staring down at his guitar with his hair in his face.