Between meeting her in 1980 and sweeping her in 1984, there was growth and development and work. I arrived at Hialeah Miami Lakes Senior High in the fall of 1983 with determination and enthusiasm. There was much to do, and I wasted no time in pursuing goals I’d set throughout the summer. Physically, I was a different animal. Those who knew me as JC’s little brother were surprised by my transformation. I was now a fifteen-year-old sophomore, recently delivered from baby cellulite and small breasts. I had grown six inches, lost about fifteen pounds and toned up during my freshman year. A sensible diet—no more pasteles de guayaba y queso from my parents’ place of employment, Tres Monitos Bakery—calisthenics, endless running and a Hungry Heart were major factors.

I will always be grateful to Danielle Beauvais, a lovely, precocious and preternaturally buxom Haitian princess who sat across from me in English, as we read about Perseus and Andromeda. She spoke these words to me at the end of eighth grade: “You’d be good-looking if you weren’t so fat.”

I set about my business and took care of it efficiently. By the time the first pep rally came around, I was sophomore class president, practicing with the JV baseball team, involved in theater and music, and a member of many service and social clubs. I was the younger brother of a popular senior, no doubt a useful perk, but much of my success came from my own ambition and hard work. I now understand that much of my achievement in those first months stemmed from the need to impress her. To show her I was back in town and staking my claim. She liked confidence and strength and sensitivity and humor and intelligence and talent. I was working on it, but so much of the former buckled at the sight of her.

I saw Her for the first time in front of the “Little Theatre,” our school’s cozy, informal playhouse where drama classes were held, and smaller productions staged. It was the first week of school. (I had not seen her since her Quinces Celebration two years before. I was my brother’s plus one at that gaudy ritual, God bless him. She floated out of a carriage, literally. A Hialeah Cenicienta. She made up for it all by singing “The Rose” for her doting audience, as I sat in a corner of the banquet hall, pounding El Bochero cidra, with tears streaming down my chubby cheeks.)

It had been two years, but it all came back in a miserable tsunami. In her presence, I still saw through pudgy eyes, and my cheek tingled with the stamp of that condescending pinch she bestowed on me the first time we met. She greeted me warmly and left out the pinch. Her look, extended and penetrating, was full of useful information. I was no longer the plump half-pint, and she instantly welcomed me as a prospective suitor. She’d heard the stories of my enduring passion, and I could detect a trace of curiosity and amusement, but I concealed my feelings as best I could.

I quit the baseball team to pursue my acting career. The things we do. What a ruse. It was all for her, for a possible us. My father’s heart broke into a thousand rum-soaked pieces, and I hated doing it to him, but my obsession eclipsed all, and involuntary callousness, rebellion and self-sabotage were sometimes the unintended weapons and armor of choice.

The Glass Menagerie was to be staged the following month.

She would play the part of Amanda, the mother, tragic old southern belle and nag; Hilda would play piteous Laura, the crippled, criminally shy daughter; Edgar would play Tom, the son, provider and poet, desperate for escape; and Guy would play Jim, the gentleman caller.

Mr. Boyd, the drama teacher, was the kindest man with the darkest sense of humor. He was soft spoken and effeminate with a sharp tongue and all the patience in the world. I met him early in the year, and, like other thespians, grew to love him. He was predictably dramatic, and we’d all get a kick out of his monologues, lectures, soliloquies and verbal lashings. His productions were always first-rate, and he took immense pride in all of it, from make-up and sets to script selection and performances.

My brother was assistant director on Menagerie, and I was allowed to watch tidbits of several rehearsals. The poor soul had no idea what he’d be dealing with months later. He’d eventually cast us TOGETHER in our spring production of All Because of Agatha. I played Flip Cannon, a young, cocky journalist, and she played Madame LaSolda, an older, loony spiritual medium. We missed a hundred cues weekly, making out backstage like two starving Dickensian urchins, ravenously devouring a crust of bread, smothering each other among props, lying on dusty wrestling mats softened by costumes and pillows beneath dangerous lighting rigs. We could not stop! My brother’s hateful hissing and outraged scolding upstaged all sound cues. I think his generalized anxiety began during that production. But all of this came later.

For Menagerie, however, I didn’t have all-access, for Mr. Boyd was stingy with unpolished material, but I was there at different stages of its development. I stared as she recited lines popping with hysteria or dripping with sadness. Tennessee Williams’s play can break your heart with its bleak prognosis of the human condition, and her voice sometimes quavered with deep sympathy for the characters and their inevitable defeat.

One evening, I watched a dress rehearsal in its entirety, one of the few prior to opening night, and I was moved in a way that made little sense to me at the time. When the house lights dimmed, sight gave way to smell, and the dark, intimate theater, redolent of the musty past—aged wood and cheap paint, antiquarian vesture and bric-a-brac, oil portraits of those long gone—came alive in another place and time. The theatre was night and the stage a tenement during the Depression. The sheer scrim with its hazy gauze created dreamlike images and sequences, and the world examined onstage was fragile and uncertain, like Laura and her tiny glass animals, poised delicately with futile sparkle on the spotlighted shelf in the heart of the living set. The characters became extensions of the actors, and the pity I felt for Tom, Amanda and Laura, only grounded and further deepened my love for my new friends. Never had the need to be part of something been so acute, and never had the fusion of art and life been so palpable.

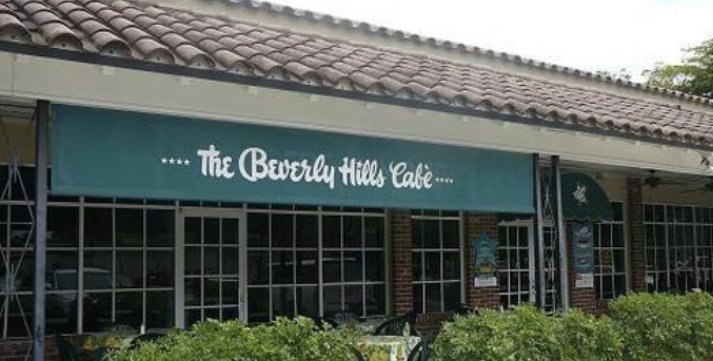

After the dress rehearsal, we all decided to meet at the Beverly Hills Café,

After the dress rehearsal, we all decided to meet at the Beverly Hills Café,

a quaint restaurant in Miami Lakes, where many teenagers spent hours of leisure. Our intimate crew began to take form that night—at least my full initiation. We all knew each other, but that evening brought about conversation and laughter that grafted the participants on a deeper level. We were seated around the table, sipping, lounging, exploring pieces of each other. James Ingram’s “Just Once” came on, and I clearly remember the emotion. That syrupy gem serenaded us from hidden speakers in the plastic flora, its melody reminding me of that bleak but beautiful final scene in The Last American Virgin. I was overcome.

The waitresses at The Bev were veterans of the hospitality business, and never hesitated to include alcohol with dinner, especially if it was for a group of polite, fun-loving kids! It was a different time. We had polished the first carafe and were looking for our waitress when Doris walked in with my world at her side. Although a few years older than she, Doris spent most of her time hanging around her little sister. And Little Sister looked radiant that night, her skin glowing, softened by petroleum jelly—used for stage make-up removal. She wore comfortable sweatpants and a snug little blouse that accented her shape with intimidating accuracy. Also present that night were Edgar, my brother, Hilda, and Heidi, an old friend who was like family to my brother and me.

Edgar was talking about the show and the poetic realism of Tennessee William’s work. He was passionate about art and expounded on its merits constantly. He was the only smoker in the group and had an elegant calmness about him that I admired. He was clever and kind, a good friend.

“Betty, can we get another carafe of White Zinfandel?” he asked.

We drank the stuff in high school.

“Sure, son. Can I get the rest of you anything else?”

No, we were fine and happy in our mildly intoxicated state, and our table blossomed with affection and the kind of talk that becomes physical in its delivery: an anecdote concluded with a warm palm on a thigh, an expression of admiration with a head on a friendly shoulder. I sometimes marvel at how open and expressive we were. When did people become afraid to touch each other?

I couldn’t believe I was socializing with this crowd. I couldn’t believe she was sitting two chairs to my right. I kept filling my glass and listening without saying much, for I was committed to stealth and discreet strategy.

“Why are you so far away?” she asked abruptly, with keen knowledge of my curse.

“It’s not on purpose,” was my best response.

Was she talking to me? How could she pin me with such force in public? She was smiling in a way that tugged at my fragile ego, and I knew this could not be for real. She was playing with me in her coquettish manner, eating my discomfort like the mozzarella marinara before her, pulling at the stringy cheese like muscle and sinew, a feline banquet, languorously licking the blood-red sauce from her fingers.

“Pass the bread, please,” she continued, and I did so with stolid motion, afterwards turning to Edgar with a comment about his portrayal of Tom.

“You nail that last monologue every time, Ed. It’s so intense, man. And the way Boyd and J.C. light that scene, that single spotlight! It gives me goose bumps.”

We finished dinner at The Bev on a pretty note,

We finished dinner at The Bev on a pretty note,

walking out with ruddy cheeks, warm exhaustion and some newly excavated emotional depth and connection. The wine enhanced our long day, and we sauntered to the parking lot with a heavy shuffle, chuckling and branching in all directions towards our cars. I watched her walk away, and for the smallest of moments, she looked back and gifted a smile at my laser gaze. I reciprocated, and her hazel glint disappeared behind a lock of chestnut hair.

Some parting words were thrown listlessly as we got into our rides. One by one, the cars shrank in the night. My brother and I secured a ride from Heidi.

“Don’t move yet, Heidi,” I pleaded.

“What’s wrong?” she asked.

“I want to give them a head start. Could we drive by?”

“Sure. I don’t mind. If you want to”

“I really want to.”

“Could you drop me off first, please?” spat my brother, wanting no part of it.

Heidi knew everything. “Come on, JC. What’s the big deal? I’ll only make one pass. It won’t take long.”

“Yeah, one pass,” I added.

“Make it fast. For the record, this is stupid.”

Driving by her house was something I did to press on the pain once in a while. It began three years earlier, when my mother would, on occasion, and at my urgent request, drive by Her house after church on Sunday mornings. I never lost the taste for it. But I preferred the night, when a rosy, dim light shone from her window, and the mystery of her nocturnal rituals unraveled slightly in fancy. What happened beyond that bedroom wall when it was safe and dark, in that space where solitude forced tender probing and all movement became naked and supple?

As the car drove down her street, my mouth became dry, and my throat tightened. My pulse intensified to a full throb and I begged Heidi to slow down just a bit. I took in the house first and then fell on her window and stayed there a few moments. My eyes pierced the half-opened blinds with strained effort, but not even a passing shadow could be seen, not a single hint of her revealed through the latticework of window bars and trees. At the property line, the car accelerated, taking me lifeless from the only place I wanted to be. Only the build-up, ripe with hopeful, expectant anxiety brought any pleasure, but I’d deal with the heavy aftermath over and over again, just to live through that brief visceral burst and hurt with fruitless proximity.

On the drive home I thought of her sleepy face in the morning, sharing an intimate conversation by her locker, opening night of The Glass Menagerie, her smell of moist earth and dried flowers, kissing her downy mound after a long school day, the song “Tea in the Sahara” by The Police… It was a thought stream that swirled the real with the absurd, the innocent with the raw, the adoring with the concupiscent, leaving me swollen in the back seat, armed to the hilt, with little to fight for.