Editor’s Note: The passage and photos are an excerpt from the author’s Traversing Haiti, an account of the photographer’s 25 trips through Haiti from 1984-2000, during its trying years of transition.

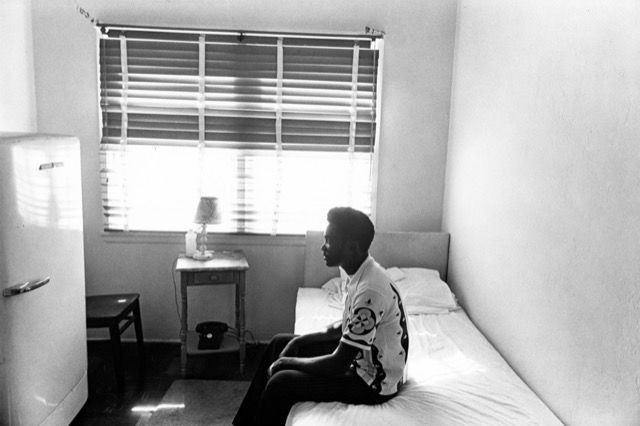

After dismissal from Krome Resettlement Camp, many Haitians were housed at the Metropole Hotel in South Beach’s newly recognized art deco district; the area was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1979. In the 1970s, the Metropole Hotel had catered to wintering Hasidic Jews, but suddenly it became government housing for the overflow numbers of Haitians who were transitioning to life in America. Throughout the Metropole’s three floors, doors to the small rooms were left open, making the boxy hotel village-like and cooler and breezier as these new immigrants inched closer to freedom.

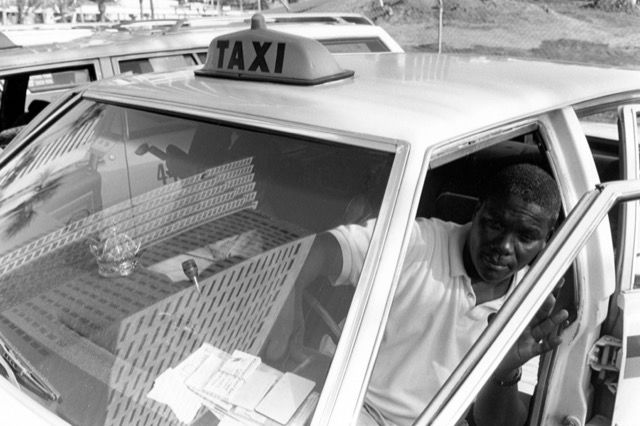

Like the Cubans who arrived during the boatlift era, Haitian refugees found cheap living in South Beach for a while, and then retreated to Miami’s “Little Haiti.” Those who had the financial means eventually moved to south Dade County. Many settled in the Fort Lauderdale area or found work in the migrant camps near Homestead and Lake Okeechobee. Haitian numbers were relatively low. Between 25,000 and 30,000 came in 1980, but unlike the Cubans, they had no political clout. Besides suffering the fallout of bad timing, the Haitians came with their own bad luck, the unsubstantiated claim that AIDS had followed them. Poverty and fear of voodoo kept them segregated, in addition to the prejudice against their color. “Haitian” became the worst of all racial slurs among Miami’s youth.

Increasingly, I travel around Florida to see how this first-generation wave of Haitian immigrants are faring, knowing the cards are stacked against them. They don’t seem to be integrating, not assimilating as much as acclimating. America is less a melting pot than a tossed salad.

Pastor Louicesse Dorsaint presides over the Haitian United Evangelical Mission, smallest of the three Haitian churches in Immokalee. Immokalee is a migrant town near the southern shore of Lake Okeechobee, the barren and foreboding place is home to many Mexican laborers. Near the end of the service in Immokalee, Reverend Dursaint asks me to come forward to address the congregation. Watching Reverend Schambach had been revelatory; I photographed him in action in the three-ring circus tent on the grounds of the old Orange Bowl stadium in Miami that housed his traveling Holy Ghost Revival. He showed me the magic of storytelling.

I begin with Creole greetings, and then switch to English while Reverend Dursaint translates. I praise the Haitian people–this comes naturally to mind, though I am not sure how much is PR–and earnestly relate my feelings from my experiences in Haiti. I talk about waking up in the mountains in the middle of nowhere in Lina, the dirt-packed road and mist, the forest and river. I talk about how villagers appeared to me as if I had been transported to another planet, and how I was taken away spiritually and physically. I run the risk of sounding sentimental, or–worse–one who casts his effort as odyssey.

“Haitians are graceful and gentlepeople,” I hear myself say as I try to refrain from wandering into banality, to sound like a talking head. I end by saying, “Kembi fen.” Hang firm. They are appreciative, and I’m warmly welcome to stay for lunch. After all, few white people pay them such attention.

About their grace and my wonderment, I’ve long felt their elegance is a result of their living repressed lives. They maintained their strong African roots as they survived in isolation under French domination, all the while absorbing French elan. It’s a unique combining of influences.

It is as if their lives outside the church vanish. They are not the shunned Haitians who have to do the dirty work. They exude confidence here, evidence of a more promising tomorrow. They are set free to reclaim their heritage through faith. They fought Napoleon and won and have persevered. Maybe though, outside of their native land, their magic will fail and its powers wither, and they will become compromised as they melt into the American stew.