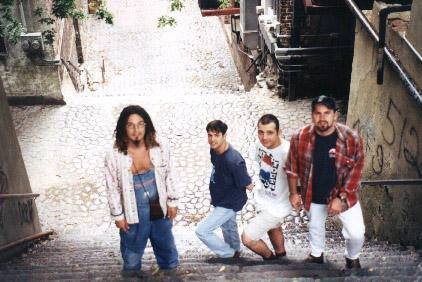

In 1994, I Don’t Know embarked on a two-week tour of the East Coast. It was a special time for us. A lot happened in that brief period, and much of it is gone, erased by time and age. It’s hard to believe it has been 25 years, and harder still to remember it all, but there are specific glimpses that stay for good, their indelible nature marked by a shared experience with real brothers. This is my best rendering of one small family portrait.

South Carolina

We drove into Charleston early. We made it to the venue in time to trade our two cases of Bud Dry for real beer. Guinness. Can. The bartender was cool. He understood our concern, our outrage. We hit it off famously. Some of the coolest people we met were those who labored behind the bar, behind the board, behind the scenes. Being sponsored was nice: free beer from Budweiser, Zildjian cymbals and sticks, Yamaha drums, Fender guitars, GHS strings, and a few grand–cash. These were gifts akin to the greatest inheritances. If you ever played in a local band, you understand. Budweiser also provided two cases of their product, delivered to each venue, for each performance. But we drew the line at beer. And we were serious. We even found it hard to pretend in front of the Bud reps. The thought of walking around, gripping long necks of chickenshit bottles, taking reluctant sips of light, pointless beer, made us queasy, angry, and we refused. It was beneath us, and we’d sooner give up our free Bud booty than compromise our refined taste. Our brewmaster elitism was pretty damn funny.

Rob, our manager, and Ferny remained at the bar, corralling the owner and soundman for business. Mark found a payphone. Tony and I went for a walk.

Taking an exploratory stroll through Charleston, down a quaint main street in the morning, after being cooped up in a pungent van (courtesy of a two day-old Subway sandwich and Rob’s baseball cap) for 6 hours—catatonic for most of it after a combustible Savannah performance fueled by too many mind erasers and Effedrine the night before—was liberating, restorative. The streets were not empty, but the spirit was peaceful, the scene idyllic. I thought of Hialeah and chuckled. This contradiction always lived in me: the love of a quiet life and the need for the dizzying mayhem. I remember this moment with such clarity. I was happy.

We found a small used bookstore.

So damn perfect. I came across a facsimile first edition of The Sun Also Rises and bought it, using a credit card I couldn’t pay. Walking out empty handed felt like a more sinister crime. I remember a freedom not unlike getting picked up early from grade school on a Friday, not for a doctor’s appointment, but for a trip somewhere special. Tony and I were in step, in more than just footing, and we looked forward to another show in a new place.

From the first day of the tour, we’d talked about making it count, not letting whatever troubles back home get in the way. We put it all on hold for a little while. Stuff could wait until we got back. There was clarity in our disposition; there was purpose in our unity. We walked and talked about the coming show, the chilling Guinness, a new audience. Imagine people you’ve never met coming to listen to songs you wrote in your bedroom. And they love them, and they dance up in your face, and they open their homes after the show, and you celebrate each other until the sun comes up. There’s nothing else like it, really. It was the way of things on the road, and we couldn’t get enough.

After taking in the town, we met the others back at the bar. We put up some posters and table tents, made sure the sound was right, and headed back to the hotel. Upon arrival, Mark and I called our better halves, bracing ourselves for the jeers and mockery that were sure to flow from the fellas (our immediate support system). The unattached brutally mocked the committed. Ball-breaking at its finest. Then we fought for the shower. Earlier, on the way into town, we had stopped by a roadside fireworks tent and purchased a bucket of M-80s and Roman candles. The first M-80 went off in the hotel room, inside the shower, while I was soaping. It was a moment of immobilizing panic and sheer terror. I couldn’t even scream, and the soap’s thud on the tub brought the house down, the laughter reverberating after the deafening blast. I never found out who did it. They refused to say.

We filmed Rob as he disrobed.

In a rush to cover up, he tripped in spastic embarrassment and fell hard. His thin body crashed to the ground with jeans around the ankles and blood on his nose. Ferny said he scored some blow. He offered me a line but didn’t tell me it was BC powder. Shit was funny at the Motel 6. It was like this for most of the tour. We argued over stupid things (becoming homicidal over disagreements about the most inane trivia), carried out the cruelest, most elaborate pranks, exploited each other’s weaknesses from every angle, relishing the ridicule and gut-cramping laughter, but we’d eventually make it onto the stage, where it was all love and sweat and harmony and groove and kinship and fucking shit up and taking names for days.

“Her shining tresses, divided in two parts, encircle the harmonious contour of her white and delicate cheeks. Her ebony brows have the form and charm of the bow of Kama, the god of love, and beneath her long silken lashes…the black pupils of her great clear eyes. Her teeth, fine, even and white glitter between her smiling lips like dewdrops in a passion-flower’s half-enveloped breast. Her delicately formed ears, her vermillion hands, her little feet, curved and tender as the lotus-bud, glitter with the brilliancy of the loveliest pearls in Ceylon…Her narrow and supple waist, which you could span with your fingers, sets forth the outline of her rounded figure and the beauty of her bosom, where youth in its flower displays the wealth of its treasures.”

On the money—I swear to God. Each of us had a brief love affair, but none of us ever touched her or let her know. These harmless, distant crushes happened in every town. This longing, too, was part of our magic.

The stage was small but elevated,

and its long, rectangular shape extended out from the back wall. It was odd for a stage, a sort of snub-nosed catwalk, a performance peninsula. There was room for the audience to get close from three sides. The set began, and, in typical fashion, there were double takes, dropped conversations, a few slightly opened mouths. The first dose of I Don’t Know: a foreign sensation for most at first, but a startling revelation by the first song’s final orchestra shot. They walked up to the stage, a few at a time, until we were surrounded by their warmth and energy. The songs played and the electricity rose, crackled. After a few songs, they were completely invested, committed, and so were we.

I remember moments where I’d look at Mark and Tony and Ferny—just eyes locking, and that familiar and familial smile of satisfaction, of a job well done, a connection and precision well-earned, a history well-established between four men who loved each other and knew they were doing what they’d always wanted to do. The set was solid, ending with a wet and sleazy 15-minute rendition of “Guadalupe”. We sold a dozen CDs and a few t-shirts—quite a score, a dinger in our minds. We reveled and cavorted and met good people. Many invited us to parties. Some invited us to their homes. Most offered party favors. All of them gave us their numbers and addresses. We were charmed and grateful, but, on this occasion, we decided to celebrate on our own. With a van full of equipment and fireworks, we headed to the beach.

We pulled right up to the sand,

stumbled out and ran to the water. The moon, the shimmer, the surf and the warm buzz. Yes, it was beautiful. The first Roman candle went off right by my ear. Yes, on purpose. I was in pain and couldn’t hear very well after that, but my initial anger gave way to hilarious revenge. I circled the van and placed an M-80 under Ferny’s skirt. Then it gets hazy. I do remember telling stories about the previous two weeks amid the explosions and bright flashes, and countless toasts about the tour and the miracle of making music (“Here’s to it and to it again. If you ever get close to it and don’t do it, you ought to be tied to it and made to do it, till you never want to do it again. So fuck it, here’s to it!”). But the rest is a dreamy montage of song, colors, guffaws, insults, Bushmill’s, tall tales, India, pain and pleasure. More feeling than memory. It was a spectacular conclusion to another wondrous night, the crowning celebration of a defining period in our lives.

This year marks the 25th anniversary of I Don’t Know’s Gullible’s Travels, the very record we were promoting during that tour. Can it be? Some days it feels like we just stumbled out of the van. Sometimes it feels like it was someone else’s life. Reaching your 50s can do that. But it’s good to still have a few snapshots archived, and even better to still feel the occasional pang with the image. Best of all I’m still making music with my brothers.