In 1968, the psychedelic era arrived in Jacksonville, Florida, on a wave of Orange Sunshine. Rock music and “acid” were part and parcel of the movement.

A year later, some teenage hippie friends and I decided to take a trip on the psychedelic bandwagon. We drove to downtown Jacksonville and scored some orange acid—five bucks a tab, which was a lot of money in 1969.

A few days later we ate the acid. It was me, my then-girlfriend, her best friend and two other guys, Doug and Chuck Newton. We hopped into Chuck Newton’s roomy ’52 Oldsmobile—which he’d painted green with some house paint and a brush—and started cruising for live music, which was easy to find in Jacksonville, especially on a Friday night.

My friends and I were music junkies—rock music was an integral element of the hippie lifestyle—plus we enjoyed communing with fellow hippies wherever we could find them. It was like a brotherhood. There weren’t many of us in Orange Park, but you could find lots of them—and lots of live music—in the Riverside district and even over on the Westside.

The five of us wound up at the Sugar Bowl, a teen club in a working-class cinderblock subdivision called Cedar Hills, where several prominent musicians were raised, including future Skynyrd members Allen Collins, Leon Wilkeson and Billy Powell. Also in the neighborhood were Jeff Carlisi and Don Barnes, future members of 38 Special, and Kevin Elson, who became a successful sound mixer, recording engineer and producer.

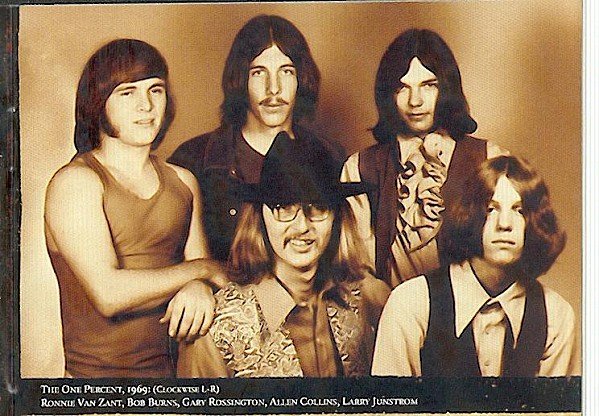

A local rock group called One Percent was performing at the Sugar Bowl that night. In the middle of the first set there was a scuffle; some local rednecks had invaded and were harassing some hippies. Someone got into a battle with an off-duty cop who served as a security guard. I heard a girl scream. A guy got stabbed, someone said. A squad of cops materialized just as the five of us were starting to get off on the acid. This was not a cool scene for an acid trip, so we hauled ass out of there and went back to staid, old Orange Park.

Westside drummer Joe Kremp, who played with a group called Running Easy, was in the audience that night and confirms that there was indeed a melee and that his friend, a harmonica player nicknamed “Doc Blues,” was the one who got knifed.

After Dickey Betts and Berry Oakley of the Second Coming—

Jacksonville’s best and most prominent psychedelic band—joined Duane Allman’s new group and left for Macon, Second Coming keyboardist extraordinaire Reese Wynans joined up with bassist-vocalist Gary Goddard. Goddard’s previous band, Wapaho Aspirin Company, used to open for the Second Coming at local “be-ins” in Riverside.

There were also be-ins on the Westside at a place called the Forrest Inn on Lake Shore Boulevard, where Allman had auditioned prospective members for his new project.

Wynans and Goddard hooked up with drummer James “Fuzzy” Land, formed a guitar-less trio called Ugly Jellyroll and started playing the Forrest Inn. This was really a good group, mainly because Goddard was possibly the best singer in town.

A few months later I was with another Orange Park pal, Greg Smith, hanging out at the Forrest Inn. It was a teen club from 8 p.m. to 11:30 and then became a bring-your-own-bottle club from midnight to 6.

The Forrest Inn happened to be about a half-mile from singer Ronnie Van Zant’s childhood home and a block from where bassist Larry Junstrom still lived. Drummer Bob Burns lived around the corner on Park Street. Guitarist Gary Rossington lived over on the other side of Cassat Avenue, about a mile to the east.

As musicians, One Percent’s members weren’t very accomplished, certainly not compared with the virtuosos in the Second Coming. Smith said the group sounded like it “just got out of the garage.” Richard Price of Bradenton band the Load, also with a later version of the Second Coming, said it was the worst band he’d ever heard.

Underdogs on the local scene, One Percent had a small but fierce following, mostly Lee High School students. Lee was about four miles to the east in nearby Riverside, close to Willowbranch Park, where some of the be-ins had been held. Lee High was also the school all the One Percenters had attended—except Allen Collins, who lived in Cedar Hills, across the Cedar River in a different school district, where he attended Forrest High.

Midway through the second set, Van Zant quizzed the crowd.

“Hey, ya’ll. We’re thinkin’ about changing the name of the group. Whatch’all think if we change it to—uhhhhhhhhh—Leonard Skinner!”

The crowd went wild.

Apparently this was some sort of inside joke I didn’t get. I leaned over and asked this tall dude a few feet away, “Who’s Leonard Skinner?”

“He’s the PE coach at Lee High who hassles them about their hair.”

I had attended Orange Park High before transferring to Central Adult downtown, so I didn’t understand the reference.

It turned out the only member of the group who actually got sent to the principal’s office by Coach Skinner was guitarist Gary Rossington, who used this experience as an excuse to quit school at 16. The others had quit more or less before Skinner arrived.

The group had just signed a recording contract with a local label, Shade Tree Records. The label was in the process of recording and releasing the group’s first single, “Need All My Friends.” Owner Tom Markham and his business partner, Jim Sutton, didn’t like the name One Percent. They asked the group to change it.

So change it they did. But the label execs disliked the new name even more, Markham said. He also said it was James Silverman, who managed the group for about 15 minutes, who suggested changing some letters to Y’s, and “Leonard Skinner” became “Lynyrd Skynyrd.” It was very hip and ironic in those days for a band to deliberately misspell its name.

Three years later producer Al Kooper, who signed the group to his Atlanta-based Sounds of the South label—which launched the group into the stratosphere—also tried to get the boys to change it. But the name stuck.

Who’d a-thunk it.