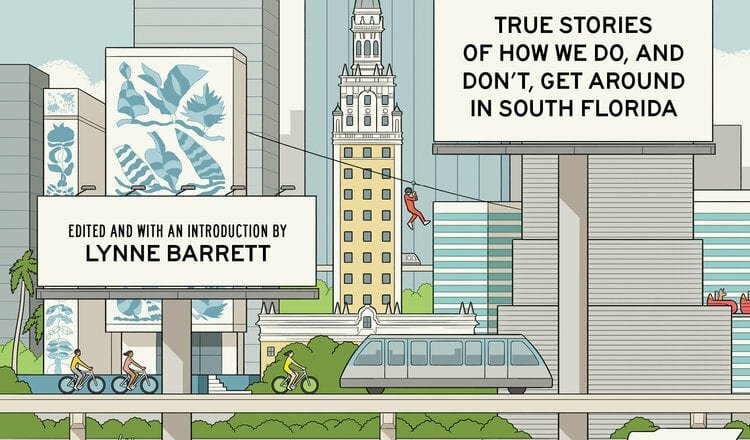

Editor’s Note: Making Good Time: True Stories of How We Do, and Don’t, Get Around in South Florida, is an anthology of more than thirty Miami transit-related stories, edited by Lynne Barrett, and featuring writers such as Richard Blanco, Jennine Capó Crucet, Les Standiford. To celebrate the book’s launch Lynne Barrett will be at Books & Books at the Arsht Center, Tuesday, October 1 at 6:30 p.m. to host First Draft, an informal writing event that turns happy hours into great stories. To get a feel for Making Good Time , here’s an excerpt from a piece by Jan Becker entitled, “Rescue”.

A month or so ago, on the last leg of my drive home I was speeding west at about 80 mph on wide, open highway, when there was a sudden explosion as an unidentified waterfowl hit my driver’s side rearview mirror, shattering it on impact and filling the car’s interior cabin with the sparkle of glass. I was uninjured, but spooked at the thought of seven years bad luck. A few weeks before that, on the way to a poetry reading in Kendall, I narrowly avoided a piano that fell off the back of a truck into my lane. Over the years, I’ve dodged large tin trash cans, barbecue grills, a couch, an industrial-sized propeller, and a load of palm trees. I’ve learned two things about commuting in South Florida:

1. No one seems to secure cargo properly, so it is best to avoid any vehicle hauling anything with the potential to become a projectile.

2. No one seems to know how to use a turn signal or hazard lights.

This morning, on my way south I noticed my battery light had switched on, warning me of its weakness. Now the light is intermittent, but switches off if I maintain a steady pace of at least 38 mph.. I try calling *347, the number posted all over the highway system for the Florida Road Rangers, who patrol in their tow trucks and rescue stranded motorists like me.

This call cannot be completed as dialed. I try again. This call cannot be completed as dialed. Traffic is beginning to pick up pace behind me. The sky has grown dark. My hazards aren’t working. I’m twenty feet from a shoulder ahead on my left, but I can’t risk getting out to push the car to safety. It feels likely that at any minute someone not paying close attention to the road in front of them will smack into me. I brace my body for impact.

The month before, after the exploding waterfowl incident, I purchased an AAA membership on the off-chance that I might need it, and, for once, I’m glad I listened to my inner nag. I fish the card out of my wallet and call them. The representative who answers is sympathetic, but firm. I have an emergency, beyond the level of assistance they are equipped to provide. It’s too dangerous to send out a tow truck to help me. “You need to call 911,” the representative tells me. “And whatever you do, stay in the car.”

I dial 911. The phone rings at least twenty-five times. The emergency dispatcher picks up, and the call is immediately disconnected. I call back. The dispatcher patches me through to Florida Highway Patrol, and the call is disconnected. On my third attempt, I finally get through to Florida Highway Patrol. Their dispatcher tells me I am not on a road where the Florida Road Rangers can assist me, because I’ve not yet gotten onto the turnpike and I’ve already gotten off I-95 North. I’m stranded in some unofficial in-between location that feels an awful lot like how I imagine limbo.

He says I should try AAA.