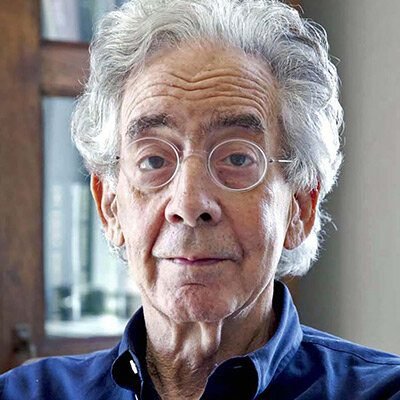

With the passing of Michael Carlebach at age 78 on August 22, 2023, I’m sharing this story about Carlebach from my personal Miami Herald archives. He was a revered photographer, mentor and educator at University of Miami from 1978 to 2005; a prolific photojournalist; and author of nine books, according to his website michaelcarlebach.com.

One of those books was “Working Stiffs: Occupational Portraits in the Age of Tintypes,” published in 2002 by Smithsonian Institution Press. I happened to catch Carlebach in his office in the early stages of preparing “Working Stiffs.” No surprise, this story was published on Labor Day in 1999.

A LABOR OF LOVE RECALLS THE WAY WE WERE

By ELISA TURNER, Herald Art Critic

Monday, September 6, 1999

A country milkmaid and a fleet of Fed Ex carriers are stomping about in Michael Carlebach’s office, joined by tinsmiths and carpenters, women rolling cigars and a man wielding a block of ice.

They make up an impromptu – and, of course, wholly imaginary – Labor Day parade, for all these workers are in fact memories of real laborers past and present. They live on in photographs that Carlebach, a professor in the Communication and American Studies departments at the University of Miami, has assembled into a remarkable record of the way we once worked.

Most of these images – except for the energetic workers of various ages, gender and color whose photos decorate a white Fed Ex box – are from the late 19th Century. They are the size of a compact mirror, printed on thin sheets of blackened iron coated with collodion.

Called tintypes, they were once hugely popular, a cheap alternative to the more expensive and fragile daguerrotype. More durable than a pair of overalls, tintypes reflected the Kodak moment of choice for thousands of American workers who paid a few pennies for the pleasure of acquiring a small self-portrait with the tools of their particular trade. You could keep it in your pocket, stamp and mail it to distant relatives, tack it to the wall with a nail.

After the rise of factories in the 20th Century, this process died out; it now seems quaint. Historians have largely overlooked these modest but resilient mementos of a very different workplace, Carlebach says. But to him, the turn of our own century is the right time to rediscover the story tintypes can tell.

“The place of work in American culture is not the same place it was 100 years ago,” he says. “Work is a way to get rich, to go to the Gap and the Shoppes at Sunset Place. It’s not so much an ideal in and of itself. Back when these pictures were made, there was a nobility to work, whether you were a fence maker or a milkmaid. These people were proud enough of what they did to present themselves as workers.

“We don’t do that anymore.”

Itinerant photographers

A gifted photojournalist, Carlebach speaks almost affectionately about the direct, artless technique of tintype photographers. They were itinerant workers likely to set up shop at county fairs and have remained as anonymous as their subjects. Often, they’d add a rough dollop of pink to a woman’s cheeks, a bit of gold to buttons. Their cloth backdrops, featuring leafy glens and shadowy castles, sometimes sagged, spotlighting their clumsy trompe l’oeil settings.

Carlebach holds up one of his favorite tintypes, a man dressed in overalls and tie holding a hammer at his side with the resolute posture of a soldier with bayonet. Then there’s the dashing young man in a sporty cap and bow tie standing next to a bicycle with gleaming spokes. “I love this guy. He’s probably a messenger, perhaps even with Western Union. You can see this man is proud of what he does. He has a good job with a modern bike. Maybe he sent it to his mom.”

Think about it. When was the last time you went out of the way to have your picture taken with your computer or speaker phone? And in family photos, workaday tools can’t compete with the charm of pets, kids on new Rollerblades and trips to the beach or the mountains.

“Labor Day,” muses Carlebach, “used to honor the working man. Now it’s a vacation. It’s also a day to go out and spend money on the things we are proud to be photographed with.”

This change in attitudes toward work had caught the attention of Mark Hirsch, senior editor at the Smithsonian Institution Press, which has published two books by Carlebach on the history of American photojournalism. Hirsch says he’s in the “talking stage” with the UM professor about his proposed book on the often touchingly earnest and intent workers in a collection of some 80 tintypes owned by New York photographer Ken Heyman, Carlebach’s cousin and co-author for this project.

“I think what Mike is trying to get at is the transition from a society that celebrates making things to a society that celebrates owning things,” says Hirsch. “To me, it really points up a respect for physical labor that is clearly evident in America before and after the Civil War and is less evident today.”

Michael Carlebach Worked with Pride

That attention to the hands-on tools of labor – rather than its fruits – is part and parcel of the post-Civil War era when the economy was battered by a severe depression, and when having a good job was a particular source of pride.

Still, it’s the pride in craftsmanship that seems most striking – and fleeting – in these shiny pocket-size portraits. Hold one in your hand, tilt it in the light, and watch it flicker in a second from a window into the past to a blurry mirror of present surroundings.

“All of our crafts are sold through Pottery Barn,” grumps Carlebach, managing a smile at his overstatement. “This is looking into a piece of American culture – one which if it isn’t altogether gone, it’s fast disappearing.”

Alison Devine Nordstrom, director of the Southeast Museum of Photography in Daytona Beach, shares Carlebach’s affection for these no-nonsense workaday images.

Innocent reflections from Michael Carlebach

She points out that the genre hasn’t completely vanished, but that its decline holds up a compelling mirror to a past that can look almost innocent to us now, especially as collectors and scholars begin to focus more on the social history embedded in antique, anonymous photographs.

“I’ve seen a couple of pictures of people peering into microscopes. I’ve seen pictures of people at the typewriter, mostly women, and I’ve certainly seen a lot of pictures of women at the stove . . . But the craft industries, like carpentry, are on the decline, and service industries are on the ascent. It’s much harder to represent a service industry. There’s something wonderful about making things, and that kind of labor we miss.”

Today’s images of labor can be packaged as artfully as the tintypes were artless. Consider the calculated sense of pep permeating the Madison Avenue-styled Fed Ex workers on the box in Carlebach’s office. These folks hold their rapid-delivery packages with the stylish fervor usually reserved for models in J.C. Crew Catalogues. Smartly turned out in navy shorts and shirts, they could be performing a corporate line-dance. These Fed Ex workers promise an indispensable alternative to that bike-riding, bow-tied messenger of decades ago, and they’re surely helping us sprint into a century during which few would notice if tinsmiths and milkmaids disappeared from the dictionary.

Just as important, despite their slick and cool efficiency, the Fed Exers represent a racially diverse population, one that’s conspicuously absent from these tintypes.

“African-Americans would have run into considerable resistance from white photographers. We were thoroughly racist back then,” says Carlebach. In the late 19th Century, however, “there were black photographers, and there’s probably a cache somewhere of tintypes of black people. There’s so much that hasn’t been discovered. People overlooked this because they thought it wasn’t worth anything.”