Former Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers’ guitarist/co-writer Mike Campbell recently published his memoir, Heartbreaker, which debuted at No. 9 on The New York Times’ best-seller list. There are a few items of interest he left out.

Tom Petty’s country-rock group, Mudcrutch, shriveled from a working quintet to a struggling trio. Suddenly the sound was thin—like their meals.

In 1972, the Allman Brothers Band—who had won a talent contest in Gainesville three years prior and were, in a sense, an inspiration for the members of Mudcrutch—would score its first top-forty hit with “Ramblin’ Man.” The Allman Brothers Band was hitting its commercial peak. Rock was becoming big business.

Meanwhile, back in Gainesville, the remaining members of Mudcrutch were scuffling. They needed to fatten their sound—and their wallets.

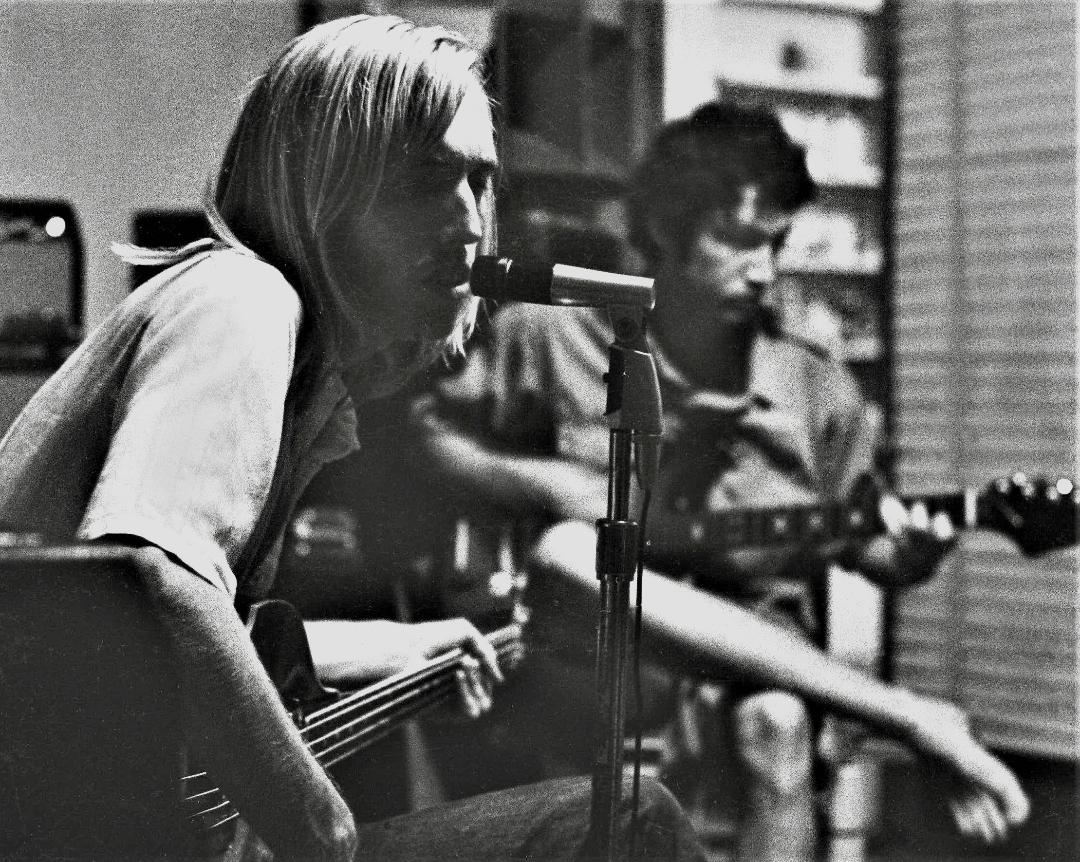

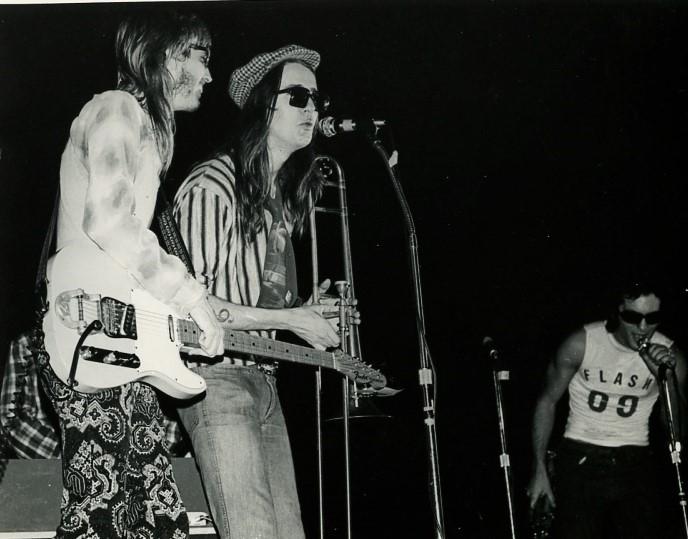

Mudcrutch, an outgrowth of Gainesville teen band the Epics, consisted of Gainesville native Petty, on bass and vocals; Mike Campbell, a University of Florida dropout from Jacksonville, on guitar; and drummer Randall Marsh, from Bushnell. Singer Jim Lenahan had been with the group for a year when he was canned in early 1971.

Guitarist Tom Leadon, younger brother of Eagles guitarist Bernie Leadon, had lost Mudcrutch its house gig at Dub’s Steer Room, a Hogtown live-music institution. For his hotheaded confrontation with owner James W. “Dub” Thomas—which cost the members their steady paychecks—Leadon was summarily dismissed.

Leadon, at brother Bernie’s behest, packed up and went west, where he quickly found work as a musician. Before long he had assumed brother Bernie’s place in Linda Ronstadt’s band.

They heard singer-guitarist Danny Roberts, formerly of Lakeland trio Power, performing in a duo with his sister at a show both acts were playing in Gainesville. Petty immediately saw the answer to Mudcrutch’s dilemma. Without consulting the others, he invited Roberts to join Mudcrutch. He didn’t know what he was getting himself into.

Neither did Roberts.

Power, later re-named New Days Ahead, had been a prominent Central Florida band. Roberts played bass but was also quite proficient on guitar, as Petty and Campbell noted at his Gainesville duo performance. He also sang lead, in a powerful blues-inflected style not unlike Gregg Allman’s.

Blogger/musician Jeff Calder, also from Lakeland, wrote, “[In] 1970, thanks to Power’s regional success, [Roberts] had made a strong reputation for himself within Southeastern musical circles, far more so than his fellows in Mudcrutch….” Calder further stated, “By no means had Mudcrutch been a bad band, but they were nebulous…. That changed when Danny Roberts moved to Gainesville. His professional experience was of greater compass. He helped the band organize more serious demo sessions, and the group’s songwriting improved almost overnight. He alternated bass and guitar with Tom, and, with the additional support of Danny’s blues-influenced vocals, the music of Mudcrutch finally received its first dimension. By April 1973, their new authority was undeniable.”

In keeping with the hippie ethic, rock groups in the early 1970s (and beyond) were generally viewed as communal entities in which all members were considered equal and had access to songwriting and songwriter royalties. This didn’t work out too well for the Who, for example, when bassist John Entwhistle would write a silly song about a spider, or for Cream, whose drummer Ginger Baker’s songs weren’t even in the same league as Jack Bruce’s.

The years 1972 and ‘73 were a turning point for music in the Anglophone world. There was a change in the wind. Bands with singular names like Jefferson Airplane, Cream, and Mudcrutch were giving way to retro-style group names, plural nouns like the Eagles, the Modern Lovers, the Ramone, the Cars, et al. In addition, long, indulgent guitar solos were going out of style. Short, sharp songs were the coming thing. It was a bit nostalgic.

What is more, there would be a return to a laser-like focus on the lead singer in groups such as Iggy Pop and the Stooges or David Bowie and the Spiders from Mars. Rock acts were emerging in which one person’s image, voice and vision was not only predominant but ruled the band. This was true for the Ronnie Van Zant of Lynyrd Skynyrd as well as for early-Sixties-inspired singer-songwriter Bruce Springsteen, whose band members and fans called him “the boss.” Springsteen released his debut album on Columbia Records in 1973.

A contingent of pop-music fans emerged who seemed to be sick of collectivist groups and were hungering for a singular individual’s worldview and philosophy. It appears that Denny Cordell saw this movement coming and decided this was what he wanted for Mudcrutch. He presumably foresaw that Tom Petty could fit into this “new wave” of music and designed an album cover that would appeal to punk sensibilities, with Petty donning a leather motorcycle jacket. Campbell comments: “We seemed vaguely lumped in with the punk scene…. We figured it was just about the picture of Tom on the album cover, the leather jacket…. The Ramones, a band I loved, wore motorcycle jackets. Must be the same type of music.”

However, Mudcrutch—following the Beatles model—had originally been presented to its musicians as a collective: all the members would theoretically be equal partners and would split all proceeds equally as well as the glory. Technically there was no leader. This hippie-ish philosophy ran directly counter to Cordell’s plan—and would have to be modified. Unfortunately, Cordell did not make his objective—to make Petty the undisputed boss—clear to all the members of Mudcrutch—perhaps because he knew there would be a revolt.

Tom Petty knew it too. In fact he didn’t like the idea.

And indeed there was a revolt—several actually. Petty would often be accused of tyrannical behavior—and that accusation may contain a grain of truth at times—but at this staage he had very little if any choice ion the matter.

Even before the group moved to Los Angeles, guitarist Tom Leadon found out who was the boss when he disobeyed Petty by taking club owner Dub Thomas to task for some offhand, disrespectful remarks he’d made, after Petty had forbade him to do so. There was no debate, no vote. Petty simply stated Leadon had to go—and it was done.

Keyboard virtuoso Benmont Tench had been a part-time member of Mudcrutch until just before the members packed up to leave for Los Angeles, when Petty somehow convinced Tench’s father—a judge—that it was actually a good idea for Tench to quit college, move to L.A. and take a stab at the music biz.

Roberts was under the impression that this was his band as much as anyone else’s. He found out to his shock, that things would drastically change, even though he was the one who had driven Petty to Los Angeles in his Volkswagen van in their first expedition to L.A. Roberts was in large part responsible for getting the group in the door at Shelter Records, where he befriended publishing manager Andrea Starr, who—perhaps unbeknownst to the others—went to bat for them at the label. But the hippie ideals the band had taken to heart as gospel were vaporized when money came calling. Investors call the shots, not lowly musicians.

Roberts says he saw the writing on the wall and quit. Campbell writes that he was relieved to see Roberts gone: “Danny could feel himself getting pushed to the side. He fought for his own songs. He campaigned for himself [via Andrea Starr] inside the label…. I didn’t like his songs, and I didn’t really like his playing anymore.”

Campbell further elucidates his thinking at this point. In his view, it was all about supporting Petty, who had the strongest songs: “Danny had to learn his place in the band. It wasn’t about him. It was about this thing we had built years before he even joined. And to me, [it] was built on Tom’s songs and Tom’s voice. That was the band. … To come in to that and make it about yourself? That pissed me off. We needed to find the humility to focus on what would make us great and get behind Tom’s songs.”

According to Campbell, Roberts also said some nasty things on his way out that put him on Petty’s “shit list” forever.

Petty immediately called Tampa-area bassist Charlie Souza to replace Roberts. He became a problem as well, but this situation was dealt with—this time—quickly and definitively. Souza, like Roberts, had insisted on contributing unwelcome material: “It was one I wrote about a spaceman and a UFO coming down,” Souza told biographer Warren Zanes. “Tom thought I was nuts….”

The next musician to chafe under Petty’s new regime was drummer Randall Marsh. Marsh made fun of label head Cordell, sarcastically referring to him as “Denny Daddy,” presumably accusing Petty of meekly acquiescing to Cordell’s dictates.

Petty hated confrontation.

According to Campbell, he preferred “covert aggression.” Campbell—who was nonetheless staunchly in Petty’s camp—uses this very term to describe how Petty managed conflict.

Despite all this, Petty insisted to biographer Zanes that even after Roberts left, he still wanted another singer and writer in the group. Petty at this point still did not see himself as the star of the show. He did his best to resist the way his band was being “packaged” by the label. Bands often do not like being packaged. It took some arm-twisting by label president Denny Cordell to make it work.

Cordell made it plain that he did not subscribe to Mudcrutch’s hippie-communalist ideology. It was a committee with too many members, not able to get things done in a timely manner, and studio time was money—a ton of money. Even if Cordell had wanted to go along with the band’s laissez-faire program, it was unfeasible to support five band members; finances had gotten to the point where he could hardly support one. And there had been very little if anything to show for it all.

That was the deal; take it or leave it. Petty astutely gauged that any deal was better than no deal. He was effectively forced by Cordell to sack the whole band. Campbell, however, whom Petty saw as indispensable, was given a last-minute reprieve.

The crux of the morale problem was that Cordell left it to Petty to break the news to the boys in the band. This would have been best coming from a manager—whom the group did not have at this stage—or ideally from Denny Cordell himself. Petty himself had to take the heat. Drummer Marsh was so upset by his sacking that he refused to speak to Petty or Campbell for decades. Petty tried to explain to Marsh and Tench that he had no choice: it was either this or the unemployment line for him—and he had a wife and a daughter to support.

After a failed experimental period using session musicians, this same ideological conflict again reared its head. Petty picked up an ostensibly new group, dubbed the Heartbreakers by Cordell, with three members of Mudcrutch—Petty himself, Campbell, and keyboardist Benmont Tench—with the addition of Gainesville musicians Ron Blair and Stan Lynch, who were participating in a demo session for Tench. Petty’s new manager, Tony Dimitriades, a London-based music attorney brought in by Cordell, hammered out a deal in which Petty would get fifty percent of the group’s earnings (on top of his songwriter royalties); the other four members would split the remaining fifty percent.

New drummer Stan Lynch, whom the members had known since his days with Gainesville rockers Road Turkey, would be somewhat mollified by this financial setup but evidently could not stomach being ordered around by Petty and would occasionally become physically menacing.

Lynch somehow managed to hang in there long enough—twenty years—to see a few humongous paydays and to connect with other L.A.-based musicians such as former Eagles member Don Henley as a co-writer. Lynch finally moved back to Florida, where he bought a ranch in Melrose, just outside Gainesville and scored a newfound career as a Nashville-based songwriter with several big hits under his belt, including a number-one country hit for Tim McGraw.

Campbell himself admits to being appalled a time or two with Petty’s newly instated imperious persona. However, he made a conscious decision to go with the flow and allow himself to become rich beyond his wildest dreams. Unlike Lynch, Campbell was able to swallow his pride. He was more than handsomely rewarded.

Campbell at one point had a family to support and was starting to get irritated about not being remunerated for all the extra work he’d been contributing to the recording project for the group’s 1979 album Damn the Torpedoes. After some urging from his wife, Marcie, Campbell finally worked up the nerve to confront Petty. Besides his co-writing, for which he would receive extra royalties, “I played all the guitar parts and some of the bass and added the extra instruments and came up with a lot of other ideas. And now I was working on the mixing too [in other words, he was de facto co-producing the album]…. So I was thinking I could get a little bit more of the pie on this one because I was such a bigger part of it…. Tom stared back at me. “Yeah, but I’m Tom Petty….” I realized he was serious. That was really his [only] answer.”

Campbell continues: “I gave him a long, hard look. It didn’t even seem to register with him. I might as well have been trying to stare down a brick wall. I turned, biting my tongue with all my might and went back to work.”

Petty by this point was clearly drunk on himself. But as Campbell and others—including Petty’s managers and producers—concluded, he had every right to be because he came to the table with the right stuff and was going to make them all rich. Damn the peccadilloes.

Campbell came to terms with this cold, hard reality. He realized he would make a lot of money if he just kept his mouth shut. Ultimate it boiled down to a simple decision: kiss the ring or get out. The others—Danny Roberts, Randall Marsh, Charlie Souza and Stan Lynch, who either could not or would not bite their tongues—would fall by the wayside. Only Lynch landed on his feet.

In 2007, after seeing the documentary film Peter Bogdanovich put together on his career, Runnin’ Down a Dream, Petty, perhaps feeling nostalgic for the old days, decided to put together a Mudcrutch reunion with a four-piece edition of the group: himself, Mike Campbell, Tom Leadon and Randall Marsh. Former singer Jim Lenahan, who had been with the group from 1970 to 1971, refused to discuss the reunion and his omission from it. Danny Roberts (1972-1975) and Charlie Souza (1975) were not consulted.

Roberts was shocked to discover his image had been airbrushed out of one of Mudcrutch’s 1974 publicity photos. “I try not to be bitter, but I can’t but be a little hurt by such an intentional snub,” Roberts said in an interview. “I thought Tom was bigger than that.”

Mudcrutch embarked on a small West Coast tour and then disbanded for several years. Petty seemed to relish playing bass again and not always being the center of attention. Jaan Uhelszki writes,

It was as if Mudcrutch allows Petty to reconnect to his younger self, a Tom Petty who still lives inside the Gainesville city limits, earning $100 a week playing Dub’s, hosting ad hoc music festivals at their base in a remote, dilapidated wood-frame house. In other words, a Tom Petty unencumbered by global fame.

Another Mudcrutch reunion followed in 2016, which comprised the final studio recordings Petty made before his death in 2017. Tom Leadon died in 2023.