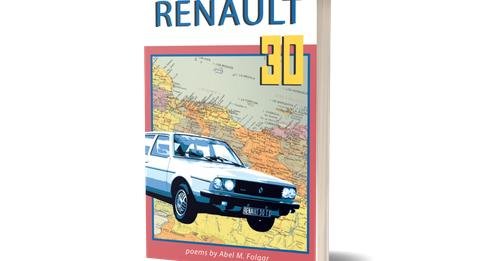

Miami based writer Abel Folgar has a brand new book of poetry out, Renault 30, published by HINCHAS Press. The book is decribed as “a sepia-toned drive through the dusty highways of 1980’s Venezuela”.

Folgar a long time local music journalist for Miami New Times, PureHoney Magazine and even this very website you’re reading, hopped on the Jitney for an in depth talk about his new collection.

What inspired your new book Renault 30?

Abel Folgar: I had the idea for a collection of poems for a few years but didn’t have, or rather, I wasn’t seeing the connective tissue required to make it happen. The COVID-19 pandemic, terrible as it was in the early days and continues to be, was a blessing in disguise for me. Transitioning to working from home freed up those commute hours and I was able to allocate that time to reading. As it happened, I reread m loncar’s (Michael Loncar’s stylized named) collection, 66 Galaxie, and that inspired me to get back to writing poems and revisiting that folder of old pieces most writers keep in a drawer somewhere.

This book’s spiritual birth was that. From there I made the connections between older poems and new ones and a memoir-like narrative emerged. I’m no gear head or car aficionado, but in paying my respects to loncar’s titular automobile, I thought long and hard about a car that had an impact on me and that was my dad’s Renault 30. My dad’s always been an excellent driver but in all my childhood memories of him tooling that French rocket through the crazy streets of Caracas, Venezuela, he’s a total icon and his soundtrack is the majestic purr of the 30’s V6.

What’s your process for writing poetry?

Most of the time I’ll have an idea or get inspired by something that I come across but the truth is, all writing as you know, takes work. In this particular book, that meant looking at poems I wrote 20 years ago under the lens of the experiences I’ve had since. It meant working on new poems with the goal of fitting them into this collection. It also meant research and recall. I have a large family, displaced all over the world since the days of the Ottoman Empire on one side, and the French takeover of Corsica on the other, but what fit here was my great-granduncle’s car accident and the generational trickle down effect. It also made me evaluate the Venezuela of my memory and the Venezuela of today. In order to keep myself from straying too far, I followed loncar’s book structure and that helped bring together these stories of a country that could’ve been more, my relationship with my family, and the automobile industry into what I’m hoping to turn into a multi-book poetic bildungsroman.

As a writer do you have to use a different part of your brain to write poetry than you do for your music journalism?

I’d have to say that I was – am – very lucky to begin my adventures in writing in print media. I was (and continue to be) blessed with incredible and patient editors who helped finetune the wordsmithing back in the days of copy by the inch. There are infinite lessons in newspaper and magazine writing that translate very well into other forms of writing – especially poetry. Thanks to that, I can lean into that world when I’m trying to physically shape a poem. In trying to adhere to a visual, the way a stanza looks, that kind of thing, the newspaper/magazine background helps. My mentor in college, the great Butler Waugh used to tell me “listen Bunkie, writer’s write.” I always understood that as a push into writing in a way that all the writing I ever did had some kind of symbiotic connection. It’s a two-way street, some of the more “flowery” language in my articles comes from wearing the poetry hat.

The Jitney published your translation of the novella, Juego de Chicos. Did getting so deep into another writer’s brain affect you as a writer?

That one had some regional challenges since the original author is from Argentina and I’m from Venezuela. Not all Spanish is the same, slang is different, etc. I enjoyed that project for that reason to be honest. I guess it’s the closest I’ll get to method acting? What helped in that project is that I have Argentinian family so I was able to vocalize the novella in that voice as I fitted the prose into English. There were some things I just couldn’t capture so there were two or three creative choices that had to be made in order to translate the overall feeling of those particular passages. It’s a great story too, and I was glad to be able to bring it to an English-speaking audience. And it’s a gorgeous book, like all Jitney releases.

Can you share a poem or an excerpt of the poem from the book with us?

Absolutely, here’s the title poem:

RENAULT 30

This is a machine, and it eats paint chips—

so many that they’ve become clogged

into an eye-clawing Jackson Pollock irritation;

slowing everything down from the accumulated

chemicals sandbagging the critical avenues

of its electrical brain. We are going to a game.

We can see it through a window but

the window somehow blocks most of the light.

We’re in my dad’s sandy champagne-colored

Renault 30, the greatest car ever imagined,

the greatest car ever made, the greatest

vessel for living that the gods of all religions—

in rare accordance—could ever create.

This might be the mechanized distillation of

liberté, égalité and fraternité but to us criollos,

in the land Bolívar made and el muérgano de

Chávez eventually destroys, this is the

Renól treinta in criollo parlance y es tremenda

máquina mi pana, sape gato y burda de arrecha.

We can feel everything crack under the weight

of dried organic matter. Everything’s opaque.

Like a Bunsen burner jetted its flame at it.

Memory assaults the whiteness of its empty

corridors—alarming shadows in its wake.

There’s a prosthetic limb caught in the

terrible moisture of a tornado somewhere.

Where and how can people buy Renault 30?

The Renault 30 paperback is currently available at hinchaspress.com and will soon be available on Amazon in print and eBook versions. I hope that, more than enjoying the poems, readers will go down Google historical rabbit holes concerning pre-communist Venezuela. In today’s atmosphere, as one of the growing immigrant groups coming into the US, I hope I can do my part to demystify misconceptions and present a positive picture of a vibrant culture that has a lot to offer. I mean, who doesn’t like tequeños, arepas or a nice glass of Ron Diplomático?