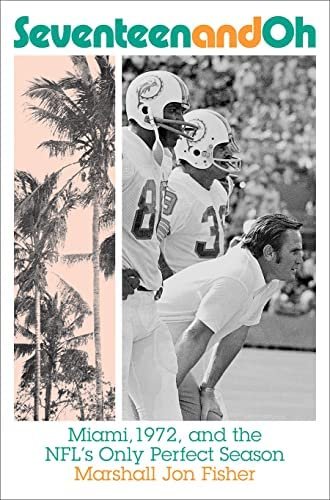

The below is an excerpt from Marshall Jon Fisher’s book Seventeen and Oh: Miami, 1972, and the NFL’s Only Perfect Season. You can see Marshall Jon Fisher at the Miami Book Fair on Saturday, November 19, at 3 p.m. in room 8201.

Every football season for the past fifty years, there has come a weekend when the last undefeated NFL team finally loses a game. More than half the time, it’s been in the first half of the season. Usually, it’s over before Thanksgiving. In 2007, it didn’t happen until February of the next year. Whether in early fall or midwinter, though, it always happens. And when it does, there is a group of old football players who can’t help but smile. They don’t, as rumor once had it, gather together and share a glass of champagne when the final zero disappears from the NFL Standings loss column. But how could they not feel a twinge of satisfaction? They are the surviving members of the 1972 Miami Dolphins, the only team in NFL history to go from opening day to the league championship without losing or tying a game.

The greatest season ever took place in a setting made for Hollywood. Miami in 1972 was a steamy cauldron of politics and sex and culture wars. As both national party conventions came to town that summer, the sidewalks and parks of Miami Beach filled with hippies, Zippies, Yippies, activists, protesters, and tourists gawking at it all. Meanwhile, the Vietnam War raged through the final bloody months of U.S involvement and Richard Nixon spent more and more time at the “Winter White House,” his modest compound on Key Biscayne, just off the Miami coast.

The relatively new Miami football team, running through its seventh preseason during the conventions, reflected the social dichotomy of the times. There were long-haired, bell-bottomed party animals with historically specific facial hair, like Jim “Mad Dog” Mandich and Manny Fernandez, along with active liberals like Marv Fleming and Marlin Briscoe—not to mention Curtis Johnson with his supernova Afro—sharing the locker room with quiet, conservative, straight-laced men, such as the quarterbacks Bob Griese and Earl Morrall. But unlike the fractious society seeming to unravel around them, this diverse group found a way to meld seamlessly into a team. The perfect team.

I was nine years old and finally on board with the Dolphinmania rising all around South Florida. My father and brother had gotten interested in the team the past couple of seasons, especially when it won what is still the longest NFL game ever, against Kansas City in the playoffs the year before, and made it to the Super Bowl (where they were humbled by the Dallas Cowboys).

Over the decades since, I have often wondered if it was merely nostalgia that made me think of this team of my childhood as unique, as having some inimitable combination of talent and character that led it to the greatest gridiron achievement ever. But no, after examining it again over the past few years, I believe this was not just another excellent NFL team. It was a rare combination of mental capacity and toughness, discipline and playfulness, youth and experi- ence, that made for the perfect team. Above all, though, this was an unusually intelligent football team. They later became a doctor, a state senator, a mayor, lawyers, successful businessmen. A sports psychologist who tested them declared that no team had ever scored higher in motivation. And one player who was traded to Green Bay the next year recalled, comparing playbooks, that he felt like he’d gone from Harvard back to high school.

Not that they weren’t tough as nails. During pregame strategy sessions, star fullback Larry Csonka would finally have enough of the subtle strategizing, crinkle his nose, already contorted by a long history of breaks, and say, “Let’s just line up and knock them on their asses.” Another player who was later traded was shocked to find new teammates who wouldn’t play with injuries. “Our guys would crawl across broken glass with no clothes on to get to the field,” he said. “That made that team what it was.” The Dolphins played the perfect season with chipped teeth, a splintered forearm, a bruised liver, a slipped disc, and broken ribs—and that was just one guy, defensive end Bill Stanfill. Others had broken arms, broken noses, you name it. Time would reveal a dark side to such intrepid- ness. Middle age and beyond would become a minefield of dementia and other concussion-related brain disorders, not to mention constant musculoskeletal pain to remind them of their old job.

It was a team with the poorest owner in the league, a team composed largely of castoffs and has-beens. One of the greatest offensive lines ever was assembled almost wholly from parts other teams had jettisoned. A number of crucial starters shared the scouts’ dismissal: “too small and too slow.” One defensive starter almost went to veterinary school instead; another, the son of physicians, arrived via the unlikely NFL breeding ground of Amherst College. It was a team saved by a thirty-eight-year-old over-the-hill quarterback, coached by a forty-two-year-old wunderkind with a leviathan chip on his shoulder. It’s noteworthy how often players echoed a similar refrain: “I wasn’t a gifted athlete,” “We weren’t the greatest athletes. . . .” This wasn’t really true, but it reflected an emphasis on intelligence, teamwork, and a work ethic forged in the struggles of many of their parents, immigrants in the American Midwest.

The fruits of that labor unfolded in the unlikeliest of places. The Greater Miami area was a quiet, relatively uncrowded sprawl of communities, a far cry from what it would become in the 1980s and beyond. The name “Miami” still evoked snowbirds in polyester suits playing shuffleboard on the beach, rather than fashion models and cocaine. Previous attempts at pro football in Florida had failed miserably, and the Dolphins franchise, the state’s only major professional sports team, was still so young that most elementary school kids could remember its first season.

Nineteen seventy-two, despite ever-present racial and political tensions and continued national divisiveness about the war in Vietnam, was a simpler time in America. A simpler era in football, too, free of the trappings of a billion-dollar business. Not that the early seventies was a utopia of peace and harmony. The Dolphins marched to perfection in a season of war, political corruption, and barely veiled racism. But Don Shula managed to integrate his team—at least during business hours—and instill a sense of dedication and purpose that blinded them to anything that might distract them from his obsession, which became their obsession: to win every game until it was January 14, 1973, and their Super Bowl debacle was supplanted by triumph.

They went 17–0, and it won’t happen again,” wrote a prescient Dave Anderson in the New York Times, just days after the Super Bowl. “The chemistry is too involved, and impossible to repeat, as if the test tube shattered before Don Shula had time to analyze the formula.” Shula’s laboratory assistants included offensive and defensive coordinators often compared to college faculty, an offensive line coach who played bass fiddle and taught his men psycho-cybernetics, and a lone-wolf scouting genius who gathered the parts no one else saw the value of. The spark to bring this perfect beast to life came the previous January in the form of a traumatic loss on football’s biggest stage. When players and coaches all reassembled the next summer, they were joined in their leader’s all-consuming drive to obliterate that failure and replace it with its opposite: ultimate victory. It all began, as every season did, with everyone running for twelve minutes in the sweltering soup bowl of July in Miami. While across the bay, as Neil Young would have it, freaks would soon streak down neon streets, podiums would rock, truth would leak, and even Richard Nixon had got soul.