It was the biggest thing since the Great Fire of 1901—maybe the biggest thing ever to hit the city of Jacksonville—except perhaps Hurricane Dora a day or so earlier.

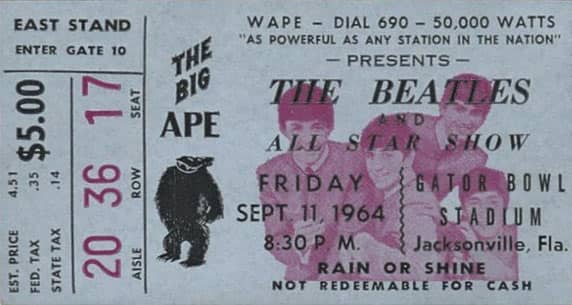

On Sept. 11, 1964, radio station WAPE-AM brought the Beatles to Jacksonville, one of only two shows in Florida (the second being an appearance on the Ed Sullivan Show in Miami).

The Gator Bowl show quickly sold out. However, Dora had left fallen trees blocking highways, preventing approximately 7,000 fans from getting to the Gator Bowl.

It was the Fab Four’s first trek into the Deep South. They were scared.

Professor Brian Ward of Northumbria University in Newcastle is working on a book about the Beatles’ complex and sometimes painful love affair with the American South. The book’s working title is, fittingly, She Loves Y’all.

After all, most of the music the Fabs emulated came from the South. The group specialized in “covering” songs by black artists such as Little Richard and Doctor Feelgood, both from Georgia; Chuck Berry, from Missouri; and Arthur Alexander, from Alabama (the Shirelles and the Isley Brothers, both from New Jersey, were exceptions, as were a couple of Motown acts, the Marvelettes and Barrett Strong).

The Fab Four also recorded songs by white country and rockabilly acts such as Texans Buddy Holly and Buck Owens along with Tennesseean Carl Perkins. Their biggest idol was of course Tennesseean Elvis Presley, perhaps the most revered southerner to hit the world stage.

Hence the group’s music was, to a large extent, a reflection of the U.S. South.

However, the Beatles, to their everlasting credit, refused to accept segregation—a sacred institution in some southern circles—and publicly stood up to support civil rights for African Americans.

Yet the Beatles had few black fans, especially in Jacksonville. One of the reasons black teens generally didn’t dig the Beatles might be because they were already familiar with many of the artists the Beatles had covered. The Beatles’ mission had been to bring black music to white kids.

Black kids didn’t need the Beatles—they already had the real deal.

Kitty Oliver, an African-American scholar and retired professor from Jacksonville who now lives in Ft. Lauderdale, was one of the rare black Beatles fans. She writes in her autobio, Multicolored Memories of a Black Southern Girl, that she could not find a black friend who would accompany her to the Beatles’ Gator Bowl concert. She went alone.

Fifty-two years later, she would appear in Ron Howard’s Beatles documentary, Eight Days a Week, and would be flown to London for the film’s premiere, where she would meet Sir Paul McCartney.

Five days before the Gator Bowl show, the Beatles—riled by insinuations that concerts in the Deep South were liable to be segregated—issued a press statement: “We will not appear unless Negroes are allowed to sit anywhere they like.” On Sept. 8, in Montreal, the group conducted a press conference in which John Lennon orally reiterated the ultimatum, citing Florida specifically.

Ward however, says the group’s anti-segregation proviso had been written into all the engagement contracts that he has had the opportunity to examine. He has not seen the Gator Bowl contract itself, but there is no reason to assume it would have been different.

The point here is that the issue had already been hammered out—and settled in writing—which raises the question: why was a public showdown even necessary?

Billee Neumann Bussard, a teen-age reporter at the scene, said that when the Beatles arrived at Jacksonville’s George Washington Hotel, they found that blacks were prohibited as guests, and this may have jolted them into action once again. The Beatles held a press conference in the hotel, where they again reiterated their refusal to perform if the show were to be segregated.

However—this is crucial, and it’s the point many writers omit—city officials insisted to local reporters that there had not been and never were any plans to segregate the show.

In his book, The Beatles: A Diary – An Intimate Day-by-Day History, cultural historian Barry Miles mentions the city’s claim that the show was never intended to be segregated. He may be one of few writers to ever report this. The next logical question would be why might the Beatles have launched an unnecessary press battle with public officials?

The Florida Times-Union did respond with an editorial dig pronouncing the Beatles’ music trash and extrapolating from their lyrics that the group’s members had neither the information nor the intellect to comment on US politics.

At bottom though, the question remains:

what would city leaders have stood to gain by segregating the concert? Perhaps it might have—at best—gotten them some political capital with racist voters. After all, Mayor Hayden Burns had run—and won—on a segregationist platform back in 1949 and managed to hang on for four terms. He had been mayor during the city’s notorious “Ax Handle Saturday” melee in 1960, in which police had been accused of allowing racist counter-protestors to brutally beat civil-rights demonstrators in downtown’s Hemming Plaza.

At this juncture, Burns, however, kept his mouth shut. He was in the midst of a heated campaign for governor and could ill afford a bad move. Alan Bliss, executive director of the Jacksonville Historical Society, said Burns would likely have “preferred to avert any kind of public-relations blunder [having] the potential to make Jacksonville appear backwards or racist.”

Promoting or enabling segregation at this time would have jeopardized the city’s receipt of federal funds, since the Civil Rights Act of 1964 had recently been signed into law by Pres. Lyndon Johnson—by all reports a vindictive man with a long memory whose ire most politicos with any sense would not wish to provoke.

Johnson happened to be in Jacksonville that very day to inspect the damage from Dora.

Having a segregated concert would also have breached the Beatles’ performance contract. WAPE-AM station owner Bill Brennan would have had to pay the Beatles for not performing, and he would likely have gone after the city for compensation. There would have been lawsuits along with very vocal reactions from 30,000 ticketholders, most of whom held no qualms about screaming their lungs out.

Certain City leaders may have been racists, but they were not, after all, complete eejits. Bottom line is there was almost nothing to gain and far too much to lose.

There is a third and very likely possibility, which Ward hints at: the controversy might have been provoked by reporters who goaded the Beatles with loaded questions implying that the southern shows would, as a matter of course, be segregated, and if so, what were the Beatles planning to do about it?

Ward states that, responding to reporters, the Beatles “kept defaulting to their contractual and moral stance that if [any shows were slated to be segregated], they wouldn’t play. When they were assured there’d be no segregation, they played.”