The following passage is excerpted and adapted from an essay titled, Growing up in South Beach.

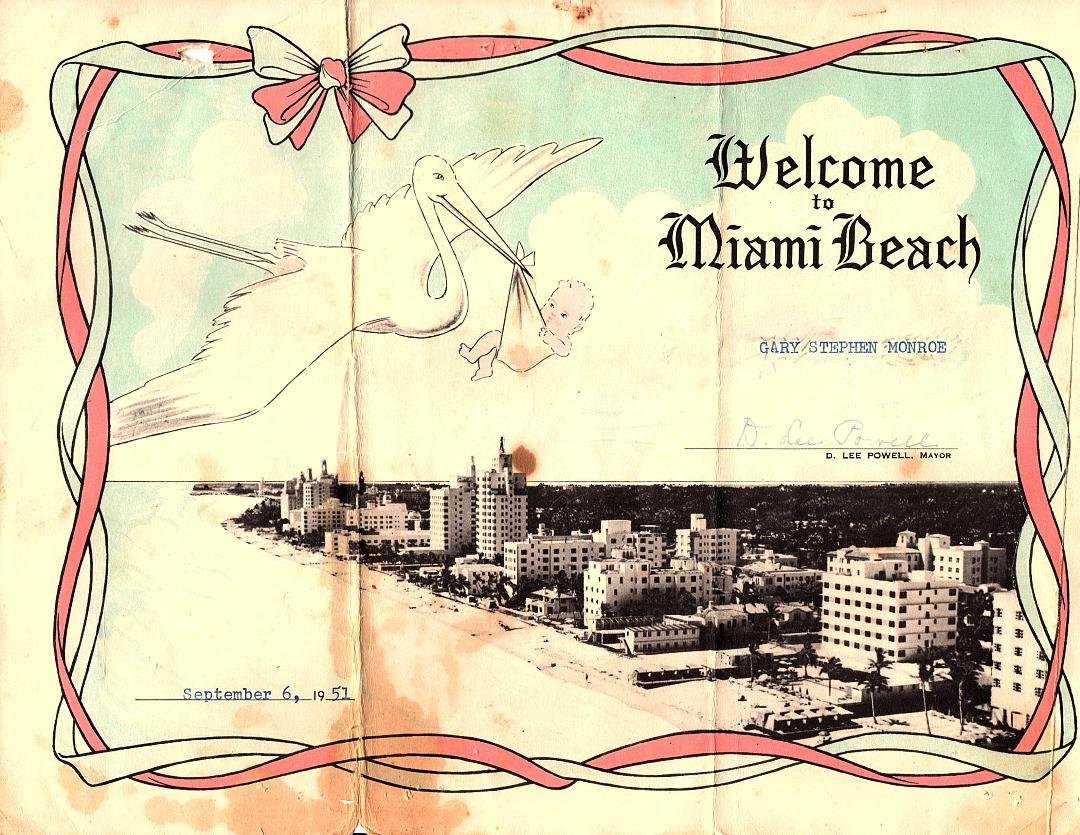

I was born in Miami Beach in Mt. Sinai Hospital in 1951. There is a badge of distinction, if not honor, to this. There is no place like this city, which one person, Mayor Leonard Haber, I think, in the late 1970s, called it the two most recognizable words in the English language. That might be a bit presumptuous, but so is Miami Beach, in a wondrous way. After all, Jesus Christ, Mick Jagger and compound interest are likewise two-word marvels.

Having been born at Mt. Sinai made me a member of a club, a Jewish one that anchored Miami Beach. However, I grew up in the city’s South Beach area during a time when it was not at all the exciting and expensive destination that it is today. Brett Ratner wrote an insightful article titled “Miami Beach Jews and the Birth of Modern American Cool.” There was nothing cool about my South Beach, barbecue weenie roasts and poolside bingo games aside.

Florida had come to life after World War II, having been fed by the popularity of automobile travel made less hectic by the new interstate highway system. Soldiers and support personnel who had trained throughout the state had experienced summer in winter. They came home with a lingering image of Paradise, and they eagerly brought their families to live in Florida. Post-war prosperity and land developers capitalized on the sunny and healthful climate. Promotional films, print ads and sales brochures spread the word, often including allusions to The Fountain of Youth. The tropical climate drew people to a relatively sparsely populated state. I-95 replaced travel by train down Florida’s east coast, delivering eager-eyed folks to Miami.

Miami Beach became like New York City, but had sand instead of snow. It was affluent, sparkling like a gem, especially during winter when the place was packed with northern Jews who had come to escape the cold and bask in the effervescent sunshine. It was the place to be in the 1950s and 1960s. It was vital and vigorous, but it wasn’t my family’s Miami Beach. My Miami Beach was South Beach when its Yiddish culture was on its way to a place of decline, only to be declared blighted in the late 1970s.

Biscayne Bay separates Miami and Miami Beach. Causeways have always linked them but as Ratner observed, the cities “were culturally many miles apart.” Similarly, Lincoln Road separates South Beach from Miami Beach proper; “proper” may indeed have been the appropriate adjective as long as it inferred to wealth and prosperity. South Beach did not become “cool” until the hyped late 1980 and ’90s. Now it is defined by expensive restaurants, outdoor cafes and clubs that are open all night. The Swinging Sixties had evaded my family. We were not associated with the trendsetters, power-brokers, or celebrities, then or later. These people made their marks above South Beach.

I recall instead playing at Washington Park after South Beach Elementary School bell rang and getting day-old garlic rolls from behind Piccolo’s; the owner’s son Dennis would dish them to us in the alley. It was one of the few restaurants in South Beach that would hold on to better days, or watch them wane. Others were The Famous, where seltzer was served in pressurized blue glass bottles instead of water, Wolfie’s, which served a plate of danishes or a bowl of pickles depending on the time of day, Joe’s Stone Crab attracted people from Miami Beach and beyond but I doubt too many from the neighborhood, Gattie’s, the best kept fine dining secret in old Miami Beach, and an array of cafeterias and delicatessens.

But the well-to-do locals ate at Ember’s Steak House, where deals were made and cigars smoked. Celebrities and the power players, and even the dangerous, dined at The Forge on 41st Street. Both are above Lincoln Road. I never ate at either. And for those who knew those times here, remember Ollie’s?

The Promised Land

The Promised Land

Growing up in Miami Beach was to grow up Jewish, in varying degrees of faith, by practice and osmosis. My family and I were Conservative Jews, as opposed to Orthodox or Reformed. However, we were all, with some exceptions, Americanized Jews. I was part of a generation far enough removed from our forbearers to assimilate, not just acclimate.

My generation was subject to mass media; television was still new and grew with us like computers, smart phones and social media do with today’s youth. We felt unified, but we were bought and sold by commercialism in much the same way as the Internet inducts children today. Nonetheless, other things bound us to one another: a combination of living on an island, being culturally different from the mainstream, and just by being Jewish. The two preceding generations knew and endured hardships that were not part of our experiences. Furthermore, we were not constantly aware of their plights even though their meanings were deeply ingrained in all of us. We felt exceptional because of our forbearers. We were coddled and protected from their World War II remembrances, as well as their passages to America through Ellis Island. Then they escaped New York, making their ways to Miami Beach, a tropical American Paradise. Many of the South Beach elderly had visible tattooed numbers on their forearms that had been there since their days in the concentration camps. It was seldom if ever discussed.

Twice a week, while I was still in grade school, I went to Temple Emanu-El Hebrew School. That was the big temple then, when Rabbi Irving Lehrman was a legendary rabbi in Miami Beach. I remember once committing to memory my haftarah, a portion of the Torah for a reading of it in that temple for my bar mitzvah. I probably was nervous during that Saturday morning service; I had to read to hundreds of well-wishers, as well as strangers, who were all there to cheer me on and to pray. A recording of my performance was made on a 78 vinyl record, but like almost everything else from my childhood, it is long gone.

I remember that Hebrew School was a reprieve for me but from what, I am not certain. I really had no responsibilities or worries, sans the anguish of growing up. Perhaps it offered roots, which I may have needed more than other children. Judaism’s history is a story based without tales of Hell. What really got my attention was “the string.” In Hebrew, it is called an eruv. I watched Hassidic Jewish men secure a string from pole to pole as they created a boundary around most of South Beach. It was rather invisible, something one would see only with intention. The eruv created a ritual enclosure that was considered a sanctified extension of their residences. This was significant because orthodoxy restricted mundane activities to be performed away from home on the Sabbath. It is still there.

My family chose the Fontainebleau Hotel for my bar mitzvah reception; it truly was a sign of my father’s “arrival” in this special place; I was still in a youthful fog. His family somewhere along the way had changed its name from Musikoff to Monroe, abandoning Russian roots while entering into American bland. He was now the patriarch of a tiny but truly American clan in a truly American place.

Neon Lights of Hotels

“Miami Beach is where neon goes to die” is a quote attributed to Lenny Bruce, a stand-up comedian who was quite popular and controversial in the 1950s and 60s. During those glamorous decades, headliners entertained here in its glitzy hotels. Indeed, the city was a magnet for them. Ever-popular entertainer Arthur Godfrey predated Jackie Gleason in heralding the city’s charms but it was Gleason who proclaimed it to be “the fun and sun capital of the world.” Gleason would often end his TV shows, saying that “The Miami Beach audience is the greatest in the world.”

A sign on the MacArthur Causeway boasted that Miami Beach was America’s Playground. Troves of tourists, a post-war booming middle class, came for a stay in Paradise. Newly rich Jews settled in the city that not too long before had barred them. “Restricted clientele” a generation earlier meant no Jews. Now snowbirds, vacationers and residents found togetherness and solace in their Jewish enclave. They enjoyed the solidarity and, depending on where they stayed, the high life. Big names, including Bob Hope, Dean Martin and Frank Sinatra performed in the better hotels, well above South Beach, along Collins Avenue during these banner years.

My father made the most of summers here. He rented two rooms at the Clevelander Hotel at 10th Street and Ocean Drive for us. It was, at that time, one of the few hotels on Ocean Drive that had a swimming pool; the beach was across the street so there was little need for these hotels to have pools. That was a luxury that each hotel above 15th Street had. The Clevelander’s kidney-shaped pool is an indelible memory of mine. Its lobby was spacious, as were quite a few of those found in other Ocean Drive hotels, generally those situated on corners. The Clevelander went on to receive fame and glory as an Art Deco centerpiece or, more accurately, for its outdoor bar.

Eventually, my father began spending summers at the Jefferson Hotel, which was at the end of Ocean Drive, where 15th Street turns left into Collins Avenue. The Jefferson was the second hotel directly on the ocean, at this end of the strip. The White House Hotel was next to the Jefferson; it was the furthest hotel that capped the northern end of the grassy stretch of Lummus Park. The Jefferson was a hybrid of sorts between those hotels below it and those above it, like the Bancroft, Sands, New Yorker and others that stretched to Lincoln Road. Eventually the Jefferson got whacked by the wrecking ball and replaced by a nondescript open-air mall-looking-thing that would have been more at home in a developing nation. The White House burned down decades ago. Now Il Villaggio stands there.

Twenty-first Street was a sort of no-man’s land during my youth. It was long known as the “gay beach.” It was a vague area between South Beach and the rest of Miami Beach. The aged but once flagship Roney Plaza Hotel defined this area during my youth. It was at the south end of the beachside promenade, a remnant of grander times even then. It was where the hotels got bigger and better. Ostentatiousness defined the four grandest hotels that were on the horizon post World War II – Fontainebleau, Eden Roc, Deauville and Carillon.

Forty-third Street bears left at Collins Avenue and then right, where it continues on through past the town of Surfside and the old and gone Motel Row in Sunny Isles, which was another world all together. A long taken-for-granted ornate iron gate was there, at the side entrance of the Fontainebleau Hotel. It was a remnant of the Firestone estate, the site that housed this famous hotel. That gate is gone, lost to the millennial building boom, during which the Fontainebleau Tower was squeezed onto those grounds.

More was better then. There was nothing shabby about the Raleigh, Shelburne, and Nautilus hotels and all the others between Lincoln Road and 23rd Street. A few below 23rd Street, like the New Yorker, Shorecrest and Royal Palm hotels had a tropically influenced art deco architecture. Those hotels north, from 30th to 43rd Streets were sleek-like-a-cat midcentury modern. The hotels below 15th Street, where Collins Avenue opens up to Ocean Drive, are humbler and crammed together, comprising the Art Deco district. Their glory lies in their facades and lobbies.

For those of us with roots in Miami the last standing iconic landmark was The Miami Herald building, which was situated on Biscayne Bay between the MacArthur Causeway and the Venetian Causeway. When it fell, so did, I imagine, the hearts of many of us. It was so indelible, it shined in the tropical light. To me though it was Epicure market on Alton Road, a few steps north of Lincoln Road, which was iconic to those of us who lived on Miami Beach. I went to the Jewish Film Festival to see The Last Resort a few years ago. I glanced around and noticed the lights of Epicure were no more… I’m still in denial.

A Real City

A Real City

Rem Koolhaas, a Dutch architect, architectural theorist, urbanist and Professor in Practice of Architecture and Urban Design at the Graduate School of Design at Harvard University, once said that “Miami Beach is an interesting hybrid because it is, on the one hand, a resort and, on the other hand a real city”. Of course he was right; Miami Beach had everything close at hand for its residents in the 1960s. Commerce flourished.

On Lincoln Road, “Fifth Avenue of the South,” the people who lived here could shop for fine apparel and enjoy a movie in their choice of theaters there or nearby on Washington Avenue, at the Beach, Carib, Cinema, Flamingo, Lincoln and Colony. They could even see a double feature for twenty-five cents at The Cameo theater. Some of these movie houses were glamorous; live parrots were perched in the long promenade of the Carib. The Cinema embodied an elegance lost to the coming age.

Residents and tourists may have socialized and caught a show at one of the many hotels along Collins Avenue above Lincoln Road. Afterwards, they could have a stacked-high pastrami sandwich smeared with yellow mustard rye bread at Wolfie’s. There they could sit in a plush red booth or along the oval-shaped counter in the center of the restaurant-deli and study the tall bright red and yellow menu with a sense of growing entitlement, as they noshed on small cheese and prune-filled Danish pastry in the mornings and dill pickles and sauerkraut in the evenings.

Epicure was an essential institution where those who lived above South Beach came to shop for better groceries but even it lost its luster. Their rugelach was still excellent as were their black-and-white cookies. Their ethnic specialty was lost because they can be bought at Publix. But it’s not the same. My mother didn’t cook: Epicure did it for her. We had quart jars of chicken soup and gefilte fish with Epicure’s labels affixed to them. They offered the best spare ribs, while the best rotisserie chicken was available on Española Way, a seedy street then. In the City’s new age (say post 2000) another demographic shopped at Epicure with aplomb; they even bought wine and flowers or lounged there while enjoying a sandwich.

Everything one needed was along Washington Avenue: Cohen’s Bakery, Butterflake Bakery and Friedman’s Bakery, Lundy’s Market and Richard’s Fruit Stand, McCrory’s and Kress Five-and-Dime stores. There was a photography shop and two photography hole-on-the-wall studios, banks, beauty parlors, jewelers, stockbrokers and doctors’ offices. The Miami Beach Record Company along Lincoln Road off of West Avenue catered to the youth who could buy 45s to play at their homes on their record players. They could be listened to in a booth before buying, and when ten were purchased, the next one was free.

The Wolfie’s at Twenty-first Street was the choice of visitors and residents alike. It was open twenty-four hours a day; that made it a prime place to go before returning to one’s hotel or home. Here customers could socialize and nosh while having a too-big piece of cheesecake or some cheese blintzes. After eating past being satiated, patrons could stroll, and maybe sit on a stool at Lee’s, an open-air fruit juice stand in front of the DiLido Hotel, while sipping on a Zombie and watching the world pass by. They could opt for a game of miniature golf on the south side of Lincoln Road along Collins Avenue.

People lined up during the heydays of Miami Beach’s deli culture to get seated; once in the doors, they waited behind red ropes that were separated by shiny silver bars into four line for different sized parties, where a jacket-clad host called the shots. Mostly the beach and the delis were gathering places. The overstuffed sandwiches meant success, metaphors for the American dream. Take a two-handed bite and you knew that you had arrive. It might have even taken you back to Katz’s Delicatessen in the Lower East Side of Manhattan. This was Jewish exceptionalism at its best.