Editor’s Note: Below is an excerpt from “Jacksonville and the Roots of Southern Rock“, written by Michael Ray Fitzgerald and published by University of Florida Press. The author will be speaking virtually at this year’s Miami Book Fair which you can sign up for here.

It seems essential to define the term “southern rock” before one can write about it. This is necessary in order to plan what goes into the text and what gets left out. So what exactly is southern rock?

Trying to define it is tantamount to going down the proverbial rabbit hole. It’s a slippery, nebulous term that can mean almost anything. On its face it appears to imply rock music from the 1970s that came from the South, but that could include anything from Wet Willie to Marshall Tucker to Lynyrd Skynyrd, acts that have little in common stylistically or sound-wise.

Author Scott B. Bomar states that the term “southern rock” was first used in the early 1970s by Mo Slotin, a writer for the Atlanta underground paper Great Speckled Bird in a review of an Allman Brothers Band concert. But the phrase didn’t come into broad usage until Al Kooper incorporated the concept into the name of his Atlanta-based record label, Sounds of the South, before he signed Lynyrd Skynyrd. Kooper was one of the first—along with Phil Walden of Capricorn Records, founded in 1969—to realize that southern talent was something that might be codified and commodified. It happened that Skynyrd fit nicely into Kooper’s concept.

Some people argue that southern rock is an amalgam of rock, blues, and country, dominated by electric guitars. However, applying this definition, the early “rockabilly” acts out of Memphis Elvis, Carl Perkins, Jerry Lee Lewis—along with Chuck Berry, Buddy Knox, and Buddy Holly might also qualify as southern rockers. One might go so far as to assert that rockabilly was an earlier wave of southern rock. There have been others. When you start digging, you never know what you’ll find down there. Variations of R&B-influenced country music go back to the 1940s with Hank Williams’s “Move It on Over” and even further, with a style called “hillbilly boogie.” Someone so inclined could probably dig even deeper.

Country and rock ’n’ roll may seem dissimilar, but they actually spring from the same Celtic roots, with rock ’n’ roll containing Africanized and Native elements, specifically drums—traditional country or bluegrass bands eschewed drums. Rock ’n’ roll was always a hybrid of country and blues, an admixture of black, white, and Native elements. Cut in Memphis in 1954, Elvis Presley’s first record was a revved-up version of Bill Monroe’s bluegrass standard “Blue Moon of Kentucky.” Elvis added African American rhythmic flourishes (that is, a gospelstyle backbeat) to his interpretation.

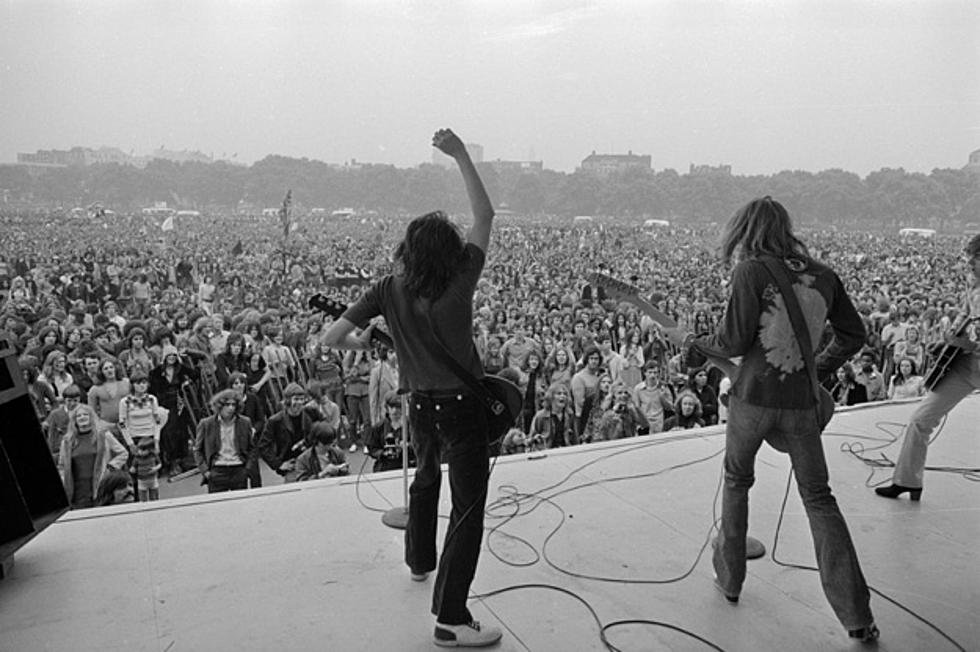

There is a big semantic problem, however, with the term “rock.” Rock is not the same thing as rock ’n’ roll, even though the two terms are often used interchangeably. Rock refers specifically to the music of the hippies and “freaks” emanating from California during the Summer of Love (1967), with the movement heading eastward. Rock culture was based on rejection of middle class values, the use of “mindexpanding” recreational drugs (mostly pot and LSD), sexual freedom, and bizarre clothes. Rock, then, was the soundtrack of the so-called counterculture. It was never monolithic to begin with and in fact embraced any style, from Hindu ragas to psychedelic “acid” guitars to blues to bluegrass along with anything and everything in between. Hence the term “rock” as a designation for a musical sound or style has no musical meaning—it was simply the sound of the counterculture, whatever that happened to be at any given moment. Hence there could be no such thing as “southern rock” or “country-rock” prior to 1967.

Southern rock, then, was music made by southern longhairs. The hair element is important, as noted in Charlie Daniels’s anthem “Long-Haired Country Boy.” Southern rock tended to have more blues and country in it, simply because that was closer to home for southern musicians.